Steve Jobs: Made in California, Designed by Japan

Jobs is remembered as an icon of American innovation, but he was deeply influenced by Japan.

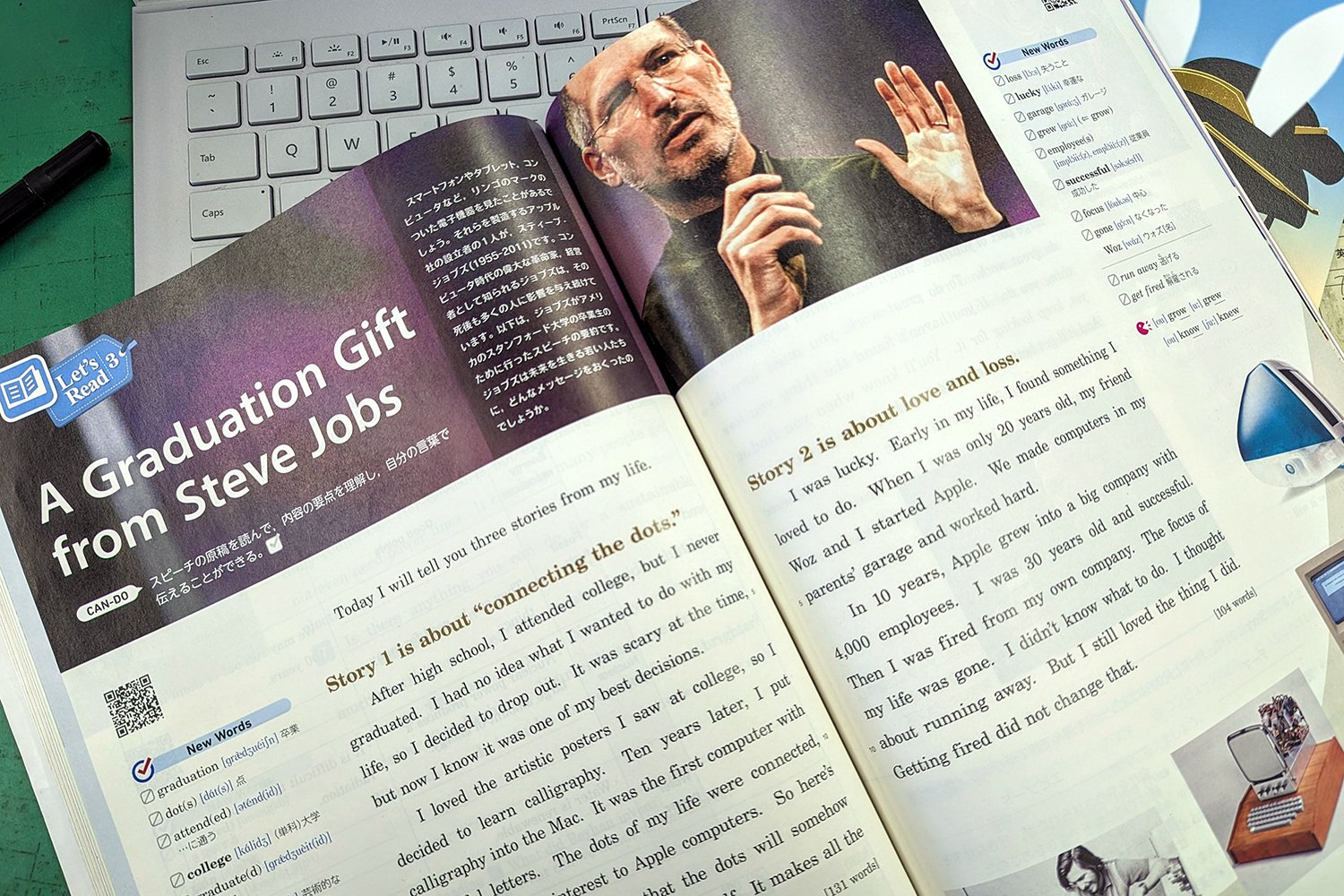

Cover photo: “A Graduation Gift from Steve Jobs” reading in the New Horizon: English Course 3 language textbook published by Tokyo Shoseki (2021 edition) sits on my desk at my junior high school, Fukui City, Fukui Prefecture, Japan (2023). Photo by Danny With Love.

Intro

Every year, as March’s graduation season approaches, soon-departing third-grade junior high school students (9th graders) across Japan read an abridged version of Steve Jobs’ landmark 2005 Stanford commencement address.

Arguably, it is the most important presentation Jobs ever gave. “I’d almost never seen him more nervous,” his wife Laurene recalled. It remains the most popular commencement speech in YouTube’s history, amassing 40 million views.

I hadn’t watched it in entirety until now, as an American teacher living in Japan. I realize that, although the late co-founder and longtime Apple CEO is remembered as an icon of American innovation, Jobs was deeply influenced by the Land of the Rising Sun.

Jobs is uniquely loved in tech-savvy Japan, remembered both for Apple’s pioneering technology as well as his personal fascination with Japanese culture. While Japan accounts for only 6.5% of the tech giant’s global sales, Apple controls over 60% of the nation’s smartphone market. Nowhere is Apple more popular.

The nation has inspired countless creative minds, like Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh and American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, but perhaps no one loved Japan more than Steve Jobs. It transformed his entire life: his religion, his diet, his fashion, and his design philosophy.

Japanophile

Jobs expressed interest in Japan early in his life, admiring his neighbors’ ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) by the artist Hasui Kawase (川瀬 巴水). He would amass his own collection of over 40 ukiyo-e, including 25 by Kawase alone. His personal print of Goyo Hashiguchi’s (橋口 五葉) 1920 Woman Combing Hair was featured prominently in the marketing materials for the first Macintosh, imbuing the machine with a sense of human elegance.

In college, Jobs studied calligraphy under the American monk, Robert Palladino. “Ten years later, I put calligraphy into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful letters,” Jobs recalled in his commencement speech.

Jobs maintained a strict vegan diet but he made an exception for Japanese food. Jobs even invented his own dish, sashimi (raw fish) and soba (buckwheat noodles) — my students were quite shocked by the unusual combination — and he sent Apple’s corporate chef to study sobamaking at the Tsukiji Soba Academy in Tokyo.

Jobs would visit Japan over a dozen times in his life, sharing the experience with three of his four children. Only in Japan was he “so relaxed and content,” recalls his daughter Lisa in the 2015 documentary, Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine.

Obsessed with Sony, Jobs zealously collected the company’s marketing materials. Upon the death of co-founder and chairman Akio Morita (盛田 昭夫), Jobs eulogized, “while he was leading Sony, they invented the whole consumer electronics marketplace.” He first wanted to call the iMac the MacMan, in homage to Sony’s Walkman.

During a visit to a Sony factory, Jobs became enamored by the employee’s uniforms, created by leading fashion designer Issey Miyake (三宅 一生). Jobs adopted a personal uniform of Levi’s jeans with custom Miyake-turtlenecks. According to biographer Walter Isaacson, Jobs kept hundreds. His trademark look was reminiscent of samue, a monk’s daily attire.

Buddhism

After adopting Buddhism, Jobs found a spiritual mentor in the Niigata-born monk Kobun Chino Otogawa (乙川 弘文), a disciple of the world-renowned D.T. Suzuki (鈴木 大拙 貞太郎). Jobs confessed, “I ended up spending as much time as I could with him.” Kobun would eventually officiate Jobs’ wedding with his wife Laurene in a small Buddhist ceremony.

Within Apple’s first year, Jobs considered leaving to become a monk at the famed Buddhist monastery Eiheiji in Japan’s Fukui Prefecture — where Kobun himself had trained for three years — but Kobun advised Jobs to stay in California and to find meaning in his current life.

According to Kobun, Jobs once told him, “I feel I’m enlightened.” When asked for proof, Jobs presented Kobun a computer board. Instead of Buddhist studies, Jobs found enlightenment through invention.

Totally consumed by his newly-founded company, Jobs stopped visiting the Los Altos Zen Center — where he had met Kobun — in 1976. Apple was the “focus of my life,” Jobs recalled.

Jobs never surrendered his ego, which is what made him a compelling salesman. Jobs accomplished what only an American Buddhist could, he transmuted the private self into a capitalist commodity. He sold self-actualization in circuitry, mass-producing individuality, and offering consumerism as self-fulfillment.

Design Philosophy

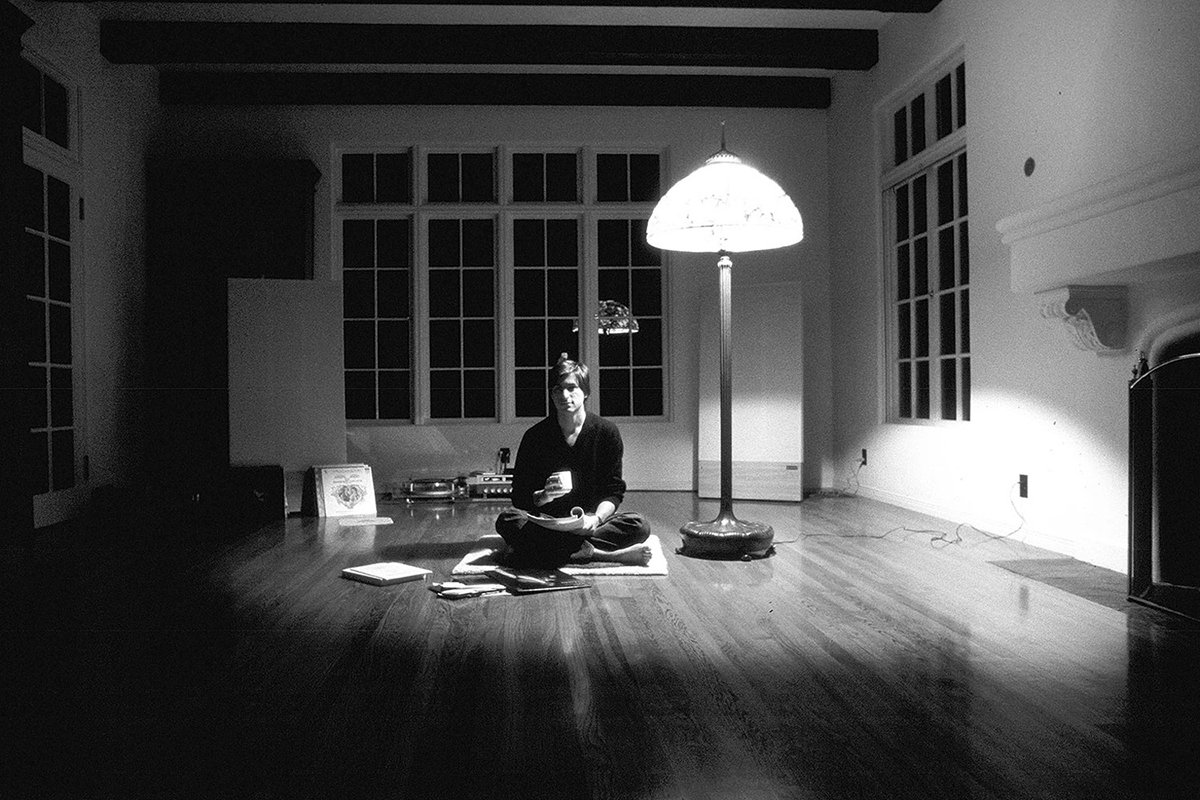

“I remember going into Steve’s house and he had almost no furniture in it,” says John Sculley, Jobs’ coworker, and Apple’s CEO from 1983 to 1993, “he was incredibly careful in what he selected. The same thing was true with Apple.”

Inspired by both Zen Buddhism and Western thinkers, Kintaro Nishida (西田 幾多郎) — Japan’s most influential modern philosopher — coined the term junsui keiken (pure experience), an unrestrained consciousness in which the division between object and subject fades away. Suzuki had a similar concept called satori.

At Apple, Jobs’ ultimate goal would be “pure” experience, as achieved through his obsession with simplicity, “a simplicity that comes from conquering, rather than merely ignoring, complexity,” notes Isaacson.

By reducing the friction between man and machine, Jobs would make technology an extension of ourselves. “It wasn’t just for you; it was you,” explains Sherry Turkle, Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT.

“He got to the aesthetic part of Zen,” confirmed Les Kaye, the head teacher of Kannon Do Zen Meditation Center in Mountain View. Jobs’ college friend Daniel Kottke agrees, “You see it in his whole approach of stark, minimalist aesthetics, intense focus.”

Apple’s hardware was minimal, even austere. “I have always found Buddhism, Japanese Zen Buddhism in particular, to be aesthetically sublime,” praised Jobs, “The most sublime thing I’ve ever seen are the gardens around Kyoto.”

According to his local chauffeur, Hiroshi Oshima (大島浩), Kyoto’s Ryoanji — home to the most famous Zen garden in the world — was one of Jobs’ favorite places to visit.

Jobs was similarly controlling, observed Isaacson, who wrote, “Being in the Apple ecosystem could be as sublime as walking in one of the Zen gardens of Kyoto that Jobs loved, and neither experience was created by worshipping at the altar of openness or by letting a thousand flowers bloom.”

Explaining Apple’s success, Jobs argued, “I don’t think it’s that profound. I think most people in the technology world don’t pay attention to design. They don’t know anything about design, they don’t care about it.” He declared, “It’s not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.”

At Apple, Jobs pioneered the concept of user-experience. Famously, he had a rule that any action must be completed with no more than three clicks. About the Macintosh, Jobs boasted, “You can sit your grandmother in front of this computer and she’ll figure out how it works.”

The British product designer Jony Ive was recruited by Apple in 1992. He and Jobs would collaborate closely, seamlessly combining Ive’s Bauhaus training with Jobs’ Zen passions. Ive produced some of Apple’s most memorable devices, including the final design of the first iPod, which fused Japanese elegance with German utilitarianism.

British industrial designer James Dyson — of vacuum fame — praised Jobs for his “intuitive risks.” Jobs argued, “It’s not the customers’ jobs to know what they want.” Like a sushi master serving an omasekase (chef’s choice) course, he could perfectly anticipate and satisfy every desire.

Revolution

Upon the launch of the Macintosh, Jobs proclaimed, “By building affordable personal computers and putting one on every desk, in every hand, I’m giving people power. They don’t have to go through the high priests of mainframe — they can access information themselves. They can steal fire from the mountain.”

“I’m a tool builder. That’s how I think of myself,” Jobs realized, arguing, “if you give [people] tools, they’ll do wonderful things with them.”

Not everyone agreed. “The notion that a personal computer will set you free is appalling,” decried computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum in 1984.

Apple ushered in a modern age, characterized by “a relentless slide into disembodied cyberspace” replacing “tangible experience,” notes Gillian Tett for the Financial Times. Today, smartphones are recognized as objects of distraction, addiction, and anxiety.

Jobs frequently cast Apple as liberatory, but the man himself was conspicuously apolitical. He adopted his personal mantra — “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” — from the Whole Earth Catalog, a hipster magazine, described as both “very libertarian” and “deeply consumerist,” that had been popular throughout the 1970s.

While against public charity and even caught in financial fraud, Jobs claimed he was never interested in money. Clearly, he thought Apple was his greatest contribution to humanity.

“The only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work, and the only way to do great work is to love what you do,” Jobs proclaimed. He died in 2011, amidst his second battle with cancer, at the age of 56. Apple’s devotees and detractors alike lamented that the company had lost its magic.

While he was described as deeply flawed by those closest to him, it’s undeniable that Steve Jobs inspired an entire generation. And whether he truly believed in his own PR spin or not, there is no question that he revolutionized how we interact with our world today, and for that we must thank Japan.