From Folklore to Fine Art: An Anthology of the Rabbit

Let’s dive down the rabbit hole, tracing symbolism of the latest animal of the year across time and space.

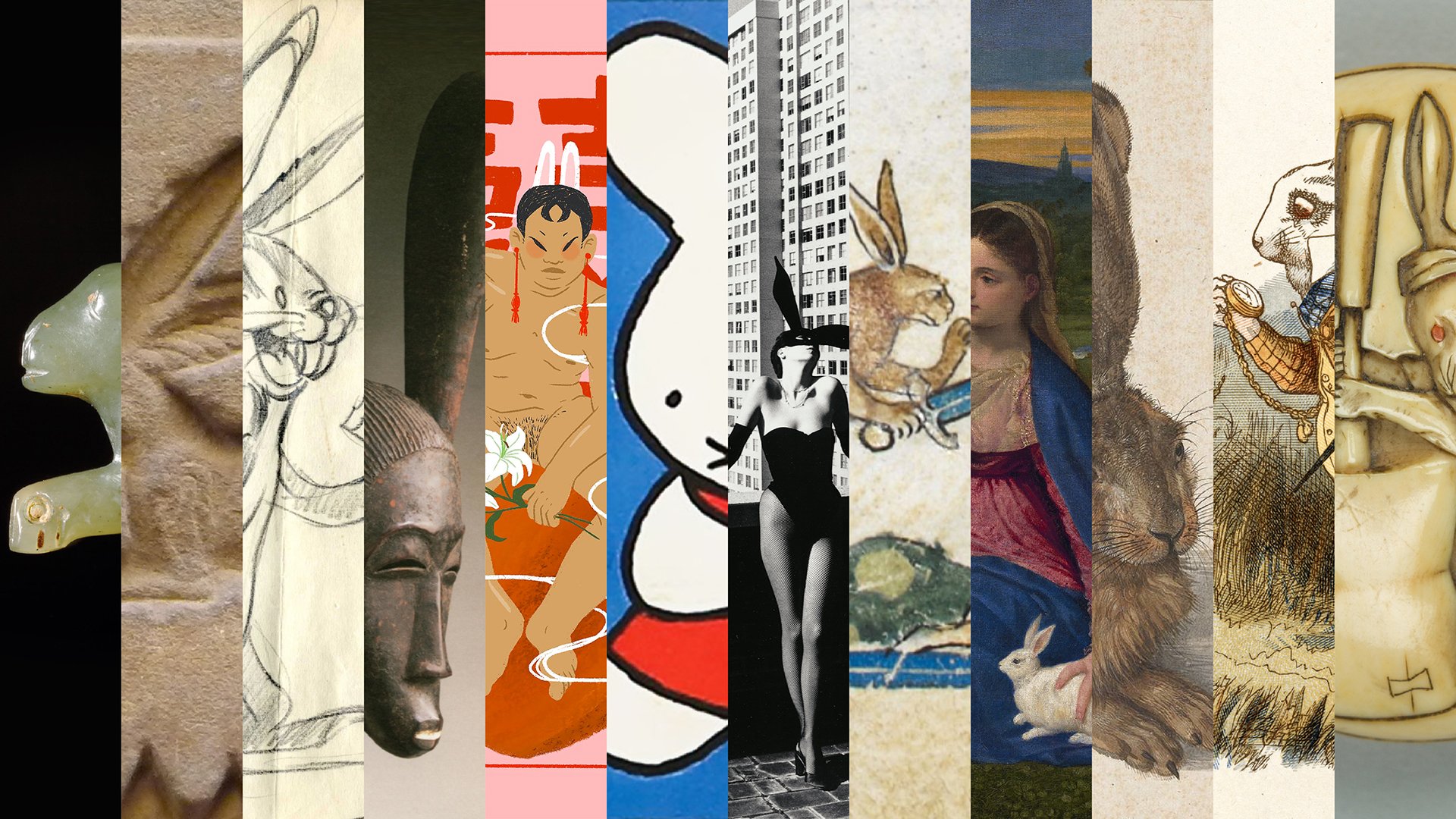

Cover photo: Digital collage of some of history’s greatest rabbits, by Danny With Love (2023).

Intro

Hoppy lunar new year! Unlike the Gregorian calendar modeled after the sun, the lunar new year follows the cycles of the moon. As this is a separate calendar, the corresponding date changes. In 2023, the lunar new year began on January 22nd.

The lunar new year is closely associated with the ancient Chinese zodiac, originating 2,000 years ago. According to Chinese myth, the divine Jade Emperor devised a great race among animals to mark time, with years corresponding to the placement of the competing creatures.

The Rat was the first to complete the race, followed by the Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. According to Chinese astrology, the year (both birth and current) determines one’s personality and luck.

2023 marks the year of the Rabbit, the fourth of the twelve animals. Previous Rabbit years include 1927, 1939, 1951, 1963, 1975, 1987, 1999, and 2011. In China, the Rabbit is said to be gentle and sensitive, as well as a symbol of fertility and abundance, hence 2023 is predicted to be a wonderful year of peace and prosperity.

Though they are distinct species, the rabbit is often confused with the hare. Today, rabbits live on every continent on earth, excluding Antarctica. They are enjoyed in the wild, as pets, and are even eaten in many parts of the world, valued for their lean meat. To my surprise, I was served rabbit while studying in Tuscany, Italy.

Blessed with abundance, the rabbit carries varying and often contradictory connotations throughout history: dwelling in the earth and sky, the rabbit is both mundane and mythical, instinctual and calculating, quick and cautious, docile and temperamental, pure and indulgent, chaste and sexy, angelic and demonic, ancient and modern.

Let’s go down the rabbit hole of history and explore symbolism of the animal.

Asia and the Middle East

Throughout Asia, the rabbit is often associated with divinity and rebirth. In addition to the great race, there is a famous Chinese tale of Yutu, the Jade Rabbit, which lives with the moon goddess, preparing an elixir of immortality with a mortar and pestle.

The vision of a rabbit on the moon is likely inspired by pareidolia, as similar tales are recorded around the world, including Japan; although here, the lunar usagi (rabbit) is often pounding mochi (rice cakes) with a mallet. The animal is celebrated along with tsukimi, an autumn festival held in admiration of the beautiful harvest moon.

The word tuzi (兔子) — translated as “bunnies” — originated as a slur for gay men in late imperial China, possibly because rabbits were thought to be androgynous and capable of asexual reproduction, thus abnormal.

According to an 18th century tale, Hu Tianbao (胡天保) was a soldier slain for his unrequited attraction to a handsome official, but forgiven and deified as Tu’er Shen (兔儿神) — literally “the Rabbit God” — upon his death. Today, queer men make pilgrimages to pray for blessing at a discrete Taoist temple in New Taipei City, Taiwan.

China is also home to the oldest discovered motif of the three hares, dating to the 6th century, in the sacred Buddhist Mogao caves near the ancient town of Dunhuang. In a testament to the influence of the Silk Road and the exchange of ideas through commerce, this infinity symbol is found across the eastern hemisphere, including an exquisite engraved Iranian (or Afghani) brass tray.

Throughout the Middle East, hares were considered auspicious animals, believed to protect women from demons while they were impure during the monthly cycle of menstruation.

The 13th century Persian poet Rumi told the tale of a lion’s demise at the hands of a meek rabbit, in a moral of self-awareness, as well as the perils of projection and narcissism:

One day, a mighty lion came upon a colony of rabbits, terrorizing the group without cease. The humblest of the rabbits accepted that they were not strong enough to defeat him. The rabbit told the lion that he was not the only predator around, but that he had competition from another lion, even more mighty than he.

Outraged, the lion demanded the rabbit take him to meet this foe. The rabbit obliged, leading him to a nearby well. The prideful lion did not recognize the furious beast in the water’s reflection. The lion was compelled to attack this ugly creature, falling to his death, drowning in the well.

The Ancient World

Called un, rabbits were common in ancient Egypt. In hieroglyphics, the symbol of the hare meant “open” or “being.” They were associated with fertility and rebirth.

A surviving Etruscan amber pendant features a figure holding two wild hares, symbolizing mastery of animals and an ability to provide. Hares were the fastest animals in ancient Italy. Greek philosopher Xenophon noted, “No one has ever seen or will ever see a hare walking.”

In Aesop’s fable The Tortoise and the Hare, the agile but overconfident hare loses a race to his more focused competitor because he takes a nap in hopes of humiliating his slow-moving opponent.

In ancient Rome, such swift rabbits were associated with vitality, and often paired with harvested grapes. One mosaic excavated in modern-day Turkey features a resting hare nibbling on fruit, located within the ruins of a public bath, on the floor of the frigidarium (cold-water room), meant to rejuvenate visitors before their exit.

Europe

Ancient Celts considered the rabbit divine, as it dwelled within the earth. A severed rabbit’s foot was believed to be a charm for good luck, an idea which long persists. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt kept one himself!

Romans bred the rabbit for food and fur, though it’s unclear who first domesticated the animal. They became popular among Pagan witches as familiars, or magical companions, and the creature was later adopted as a pet in Victorian England.

As lampooned in the 1975 film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in the margins of medieval manuscripts, illustrators depicted mighty rabbits vanquishing human foes in an absurd and comical role-reversal likely meant to entertain and motivate readers.

In 1502, the German painter Albrecht Durer created what is considered one of the finest works of the Northern Renaissance, Hase (Young Hare), in demonstration of his skills in observation, art, and mastery over nature itself.

As rabbits were thought to reproduce asexually, Christians associated the animal with the Virgin Mary, famously depicted in Tiziano’s painting The Madonna of the Rabbit. She holds the head of her miracle baby with one hand and clutches a white bunny in the other, symbolizing her chastity while legitimizing the purity of Jesus.

German immigrants arriving in America in the 18th century brought with them ancient Pagan traditions of spring renewal, including an egg-laying rabbit. As a symbol of rebirth, the rabbit shifted to represent Christ’s resurrection, redeeming humanity of sin.

Originally founded as a German-language publication by Austrian-born cartoonist Joseph Keppler, the satirical Puck magazine became incredibly influential in the United States. A 1903 cover by Louis M. Glackens depicts a greedy young girl filling her apron with all of the Easter Bunny’s colored eggs. The rebirth icon was eventually adopted by chocolatiers, with the Swiss company Lindt beginning production of golden rabbits in 1952.

Africa and the Americas

Throughout much of Africa and the Americas, the animal is depicted as a quick-witted trickster, like the Br’er (Brother) Rabbit, who is able to outsmart his larger and stronger enemies.

In an American retelling, Br’er Rabbit encounters a baby in the middle of a road. When the baby doesn’t respond to the rabbit’s greetings, he strikes the figure, only to discover it’s made of tar. Br’er Rabbit becomes trapped in the sticky substance set by Br’er Fox, who is ready to devour the defenseless creature.

“Drown me! Roast me! Hang me! Do whatever you please,” begs Br’er Rabbit. “Only please, Br’er Fox, please don’t throw me into the briar patch.” The sadistic fox flings Br’er Rabbit into the briar patch, where he was born and bred, escaping to safety.

Imported by enslaved Africans, and popularized by folklorist Joel Chandler Harris, Br’er Rabbit was later declared the “adopted hero of the American Negro slave” by Harlem Renaissance poet Arna Bontemps, as a symbol of resilience and survival.

“Tricksters,” writes Anishnaabe author Danielle Boissoneau, “have a special role in mediating humanity’s ego with humorous reflections.”

Across North America, many indigenous people tell tales of the ancestral god Nanaboozhoo, who took the form of a rabbit to steal fire for mankind. According to an Algonquin retelling, fire was deemed too dangerous for mere mortals, sealed away under the protection of a divine guardian and his daughters within the center of the earth. Nanaboozhoo was distraught to see humans cold and sick, unable to even cook their food, so he devised a plan.

Nanaboozhoo transformed into a little rabbit, then submerged himself into freezing waters, before embarking on his journey. The pitiable sight of the wet and shivering bunny inspired the daughters to welcome Nanaboozhoo to warm himself by the sacred flame, while the father guardian slept. When the daughters left the bunny alone to dry, he grabbed one of the burning sticks and fled, easily outrunning the waking guardian and his surprised daughters, returning to bestow humanity with the gift of fire.

The Aztecs celebrated Centzon Tōtōchtin, a group of “four-hundred rabbits” collectively known as the Gods of Drunkenness with harvest rituals involving an agave alcohol known as pulque. Restricted for the elite, anyone who had enjoyed too much, was said to be as drunk as four-hundred rabbits, a number synonymous with infinity.

The Dogon peoples in Mali and the Baule in the Ivory Coast, are both known for their use of stylized animal masks in ritual dances. Inhabiting the wild bush, rabbits represent chaos for the Dogon, and rabbit masks are typically used in funeral rituals.

Baule masks are worn exclusively by men and only the best dancers are allowed to wear mblo (portrait masks). The Baule people wear these masks with exquisite costumes to honor living community elders in public celebrations accompanied by drummers and singers.

As mblo are created to depict an elder’s personality and skill, rather than physical likeness, a rabbit mask likely denotes great dexterity or agility. According to art historian Susan Vogel, “The idealized faces are introspective, with the high foreheads of intellectual enlightenment and the large downcast eyes of respectful presence in the world.”

Pop Culture

Rabbits are some of the most enduring and beloved animal characters from Western pop culture, including the White Rabbit from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Peter Rabbit (1901), Rabbit from Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (1927), Bugs Bunny (1940), Thumper from Bambi (1942), Miffy (1955), and Roger Rabbit (1981).

The dawn of industrialization and globalization birthed the idea of intellectual property rights, crucial to differentiate similar products and secure profits through merchandising.

England was on the forefront of trademark protection, where some of the earliest iterations of commercialized rabbits appear, including the endearingly anxious and enchanting White Rabbit, who lures titular Alice into Wonderland, as written by Lewis Carroll and so memorably illustrated by the cartoonist John Tenniel.

Writer and illustrator Beatrix Potter was inspired by her own pet — and love of nature — to create Peter Rabbit. A.A. Milne began making stories of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, based upon his own childhood toys, although both Owl and Rabbit were produced from Milne’s imagination.

While in Europe rabbit characters were often soft and cuddly, their American counterparts were more mischievous and troublesome. Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in 1927, to separate their cartoons from feline-obsessed competitors. Oswald proved to be a runaway success but the pair ultimately lost him to partner Universal Pictures, redesigning the character as the iconic Mickey Mouse soon after.

Decades later came another influential American rabbit. Named after co-worker Ben “Bugs” Hardaway, Bugs Bunny is a creature of “controlled insanity,” according to Chuck Jones, who credited fellow animator Tex Avery for the creation of the rabbit. The team had only one self-imposed rule for the animation: to maintain audience sympathy, Bugs Bunny’s antics could only be motivated by self-defense.

“It was very important that he be provoked,” explained Jones. Like in the margins of medieval manuscripts, the humor of the classic cartoons came from Bugs Bunny exacting revenge on his nemesis, the hunter Elmer Fudd.

Inspired by artists Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, and Henri Matisse, Dutch designer Dick Bruna created Nijntje — literally “little rabbit” — better known as Miffy, as a minimalist pictogram, both innocent and comforting. The success of Miffy inspired the development of Sanrio’s Kitty-chan, internationally called Hello Kitty.

Modernity

Rabbits have shed much of their innocence within the last 150 years, reflecting the hedonism of the 20th and 21st centuries. In 1953, Hugh Hefner published the first-ever issue of the controversial Playboy magazine, featuring unabashed images of nude women. Creative director Art Paul designed the famous bowtie bunny logo soon after.

Like with the women that graced the magazine’s centerfolds, Playboy divorced the rabbit from fertility amidst a sexual revolution, successfully framing women’s sexualization as liberatory. “A girl resembles a bunny,” Hefner argued, both “a fresh animal, shy, vivacious, jumping — sexy.”

In one of his most famous works, the photographer Helmut Newton captured his lover, the model-turned-designer Elsa Peretti, dressed in a bunny costume on the terrace of her New York apartment, relaxed against the backdrop of the city’s imposing architecture, with a cigarette in hand.

“One morning, he said, ‘I want to do a picture of you.’ I didn’t know what to wear. I went to my closet and came out wearing this costume I’d worn to a party with [fashion designer] Halston. Helmut was flabbergasted,” recalled Peretti. The image came to epitomize the sex, glamor, and modernity of the 1970s.

The late Irish-Welsh sculptor Barry Flanagan devoted his entire professional career to the hare, which he employed as an exaggerated mirror for humanity. He explained, “I find that the hare is a rich and expressive form that can carry the conventions of the cartoon and the attributes of the human into the animal world.”

As opposed to the bunnies of yesteryear, Flanagan’s elastic hares possess a more demonic energy. In an anthropomorphic caricature, Flanagan recreates Rodin’s 1904 masterpiece The Thinker with a gaunt hare, bridging the divide between man and animal, contemplation and instinct.

Lastly, a stainless steel Rabbit by Jeff Koons currently holds the title for the most expensive work by a living artist sold at auction, purchased for a staggering $91 million in 2019. Created in the 1980s, Rabbit has become an icon of American excess and narcissism. It wields a carrot to its face like a microphone, or a masturbatory gesture from Freud’s own dreams. Koons uses reflective material because “it affirms that your participation is necessary.”

As the perfect antithesis to Michelangelo’s David, and a natural progression in the lineage of sculpture, Chairman of Post-War and Contemporary Art at Christie’s Auction House, Alex Rotter declares, “The end is a small bunny.”