Maria E. Piñeres’ Queer Textiles

Colombian-American fiber artist Maria E. Piñeres is queering textiles.

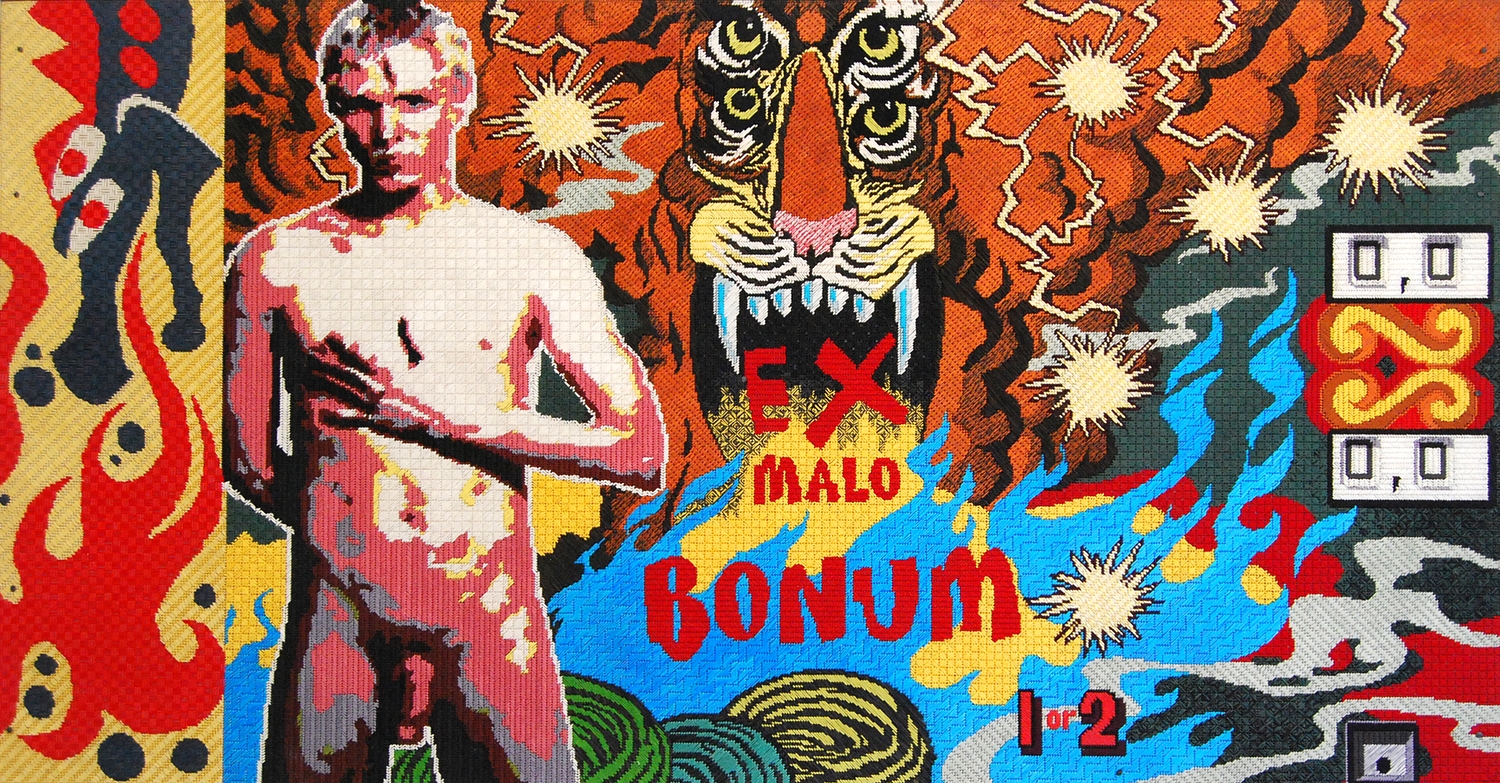

Cover photo: CAVEAT (MAY HE BEWARE), cotton floss on plastic, mounted on wood panel, by Maria E. Piñeres (2013). Via the artist’s website.

This article is part of my 30 Living Queer Artists Worth Celebrating in 2019 series. June is Pride Month, commemorating the international gay rights movement that began June 28th, 1969, with the Stonewall riots of New York. 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the event. I’m celebrating all month long!

WARNING: The following article features and/or discusses graphic nudity, pornography, homoerotica, and oral sex.

Fiber as Rebellion

Colombian born American artist Maria E. Piñeres studied painting at the Art Students League of New York and illustration at Parsons School of Design. Piñeres was raised mostly by her grandmother, who taught her needle arts, now Piñeres is expertly using fiber to challenge patriarchy and heteronormativity.

Textiles have a long history as a feminine and — more recently — feminist medium. Fiber has also proved to be fertile ground for queer artists like Zach Nutman, Cindy Baker, and Nicolas Moufarrege, who explore themes of sexuality, domesticity, and appropriation. Piñeres is working in all these aspects.

PLAYLAND

Piñeres’ most visually complex works are those from her series PLAYLAND, inspired by a now-defunct gaming arcade chain in New York City that was popular in the 1980s. The locations near Times Square sat among porn palaces, peep shows, and sex shops. In PLAYLAND, Piñeres directly combines arcade games with nude figures from vintage erotica found in the neighboring stores.

Piñeres uses cotton floss, embroidery thread, to create stitched needlepoint artworks. PLAYLAND features an eclectic use of imagery. In the series, Piñeres appropriates nude figures, games of chance, and latin text. The use of limited — but vibrant — colors creates a pop-inspired palette that lends itself well to the kitsch images.

The juxtaposition of erotica and games of chance brings to mind the casinos of America’s Sin City, Las Vegas. In fact, there is much similarity in the diction used to discuss sexual ‘conquest’ and games of chance, for instance “getting lucky,” “scoring,” and “cheating.” Casinos have a history of using sexual innuendo in advertising, often objectifying women — especially queer women — in the process. Furthermore, both gambling and same-sex relations have been traditionally associated with deviancy.

In 2004, the Las Vegas Hard Rock Hotel & Casino agreed to pay a $100,000 fine to settle a complaint with the Nevada Gaming Commission over a sexually suggestive advertising campaign, including a billboard featuring a man reaching over a topless woman on a gaming table with the caption “There’s always a temptation to cheat.” which was later revised to “Keep your mind on the game.”

Another billboard in the same campaign featured a couple of women locked in an embrace — presumably lesbians — with text reading, “Looser than your girlfriend.” playfully suggesting the hotel could provide a homoerotic fantasy for straight male customers.

Associate Professor of Advertising at the University of Georgia, Tom Reichert, wrote, “Such images of female nudity and same-sex activity, in addition to normalizing objectification of women, contribute to a “hegemonic discourse” regarding heterosexual pornography, perpetuating the notion to both men and women that women serve as things to be “used, abused, and discarded.””

As a queer female artist appropriating vintage homoerotica, Piñeres reverses the perspective by removing the heterosexual male gaze. Indeed, Piñeres depicts men engaged in sexual acts more often than women, with Freudian curiosity and a hint of voyeurism (similar to straight men’s fascination with lesbians).

This is similar to the motivations behind Japanese Yaoi, or Boys Love, manga comics depicting the romance of men who love men, which is authored — almost exclusively — by straight women. A staggering data analysis of Pornhub’s content proves women watch more gay male porn than men watch lesbian porn (although no precise figures are provided).

A female friend, who is in a same-sex relationship, explained to me, “I have watched gay [male] porn. The lesbian porn always looks like an act or fake, and it’s annoyingly loud. It’s more realistic to me than lesbian porn is I guess.”

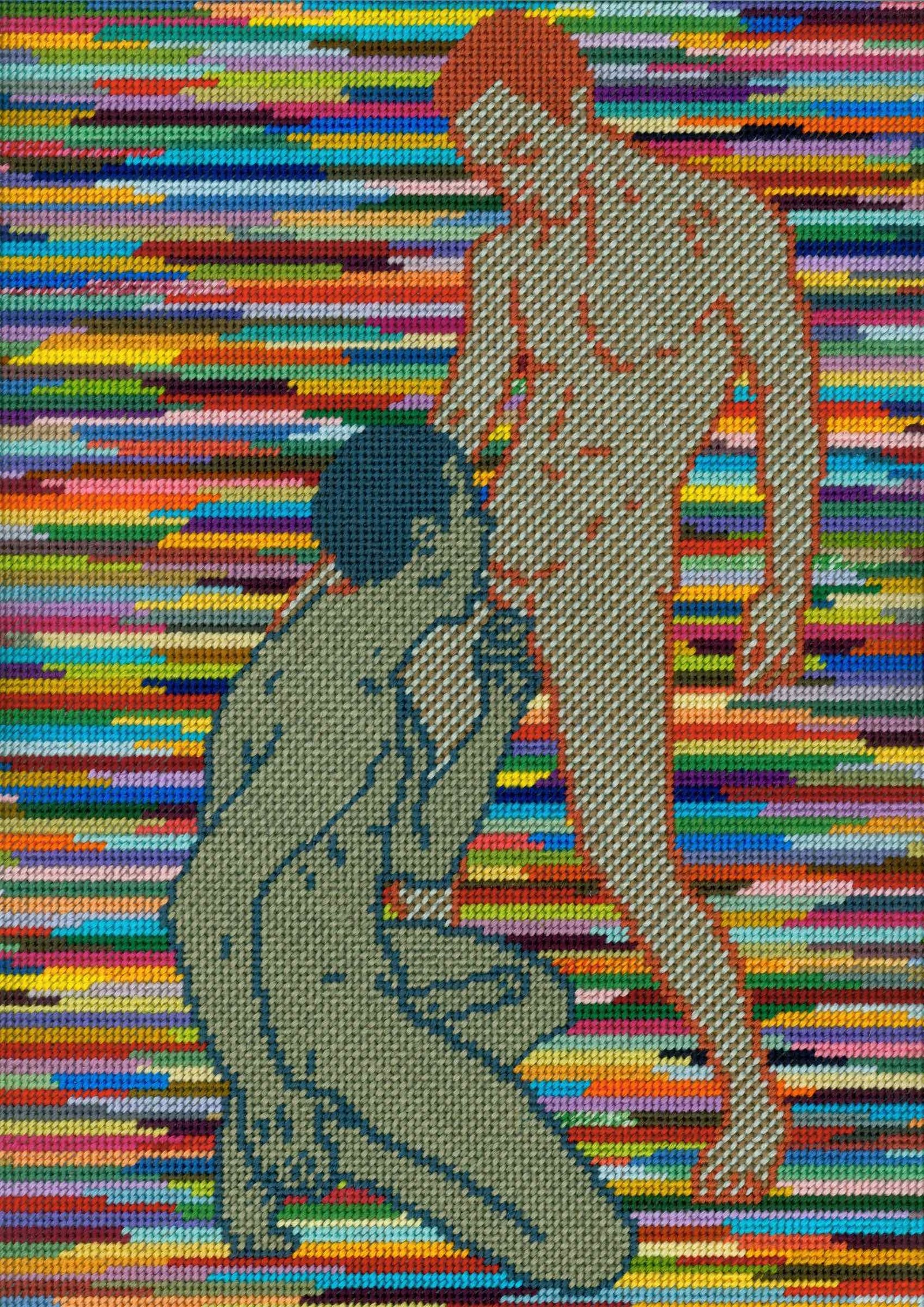

In one artwork, POSSUNT QUIA POSSE VIDENTUR, fiber artist Piñeres has created an especially sensual depiction of homoerotica, portraying three intimate nude young men with erect penises. The darkened two-toned image of the young men is encased and immortalized within the vibrant interior of a pinball machine. The men are embraced in a position reminiscent of neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova’s equally homoerotic The Three Graces.

Because of the homoerotica, the machine is recontextualized, with balls, springs, and levers suddenly bearing sexual connotations. Placed near the erections of the men, the words “POINTS WHEN LIT” read as innuendo. The men stare down at their genitals, towards the — pun intended — ball drain.

The nude men are derived from vintage erotic magazines, thus this is a performance of queerness rather than an authentic expression. The juxtaposition of sexually explicit performed homoerotic intimacy and the imagined public setting of arcades creates an idea of queerness as spectacle, similar to the fetishizing advertisements of casinos and idealized graces of Canova.

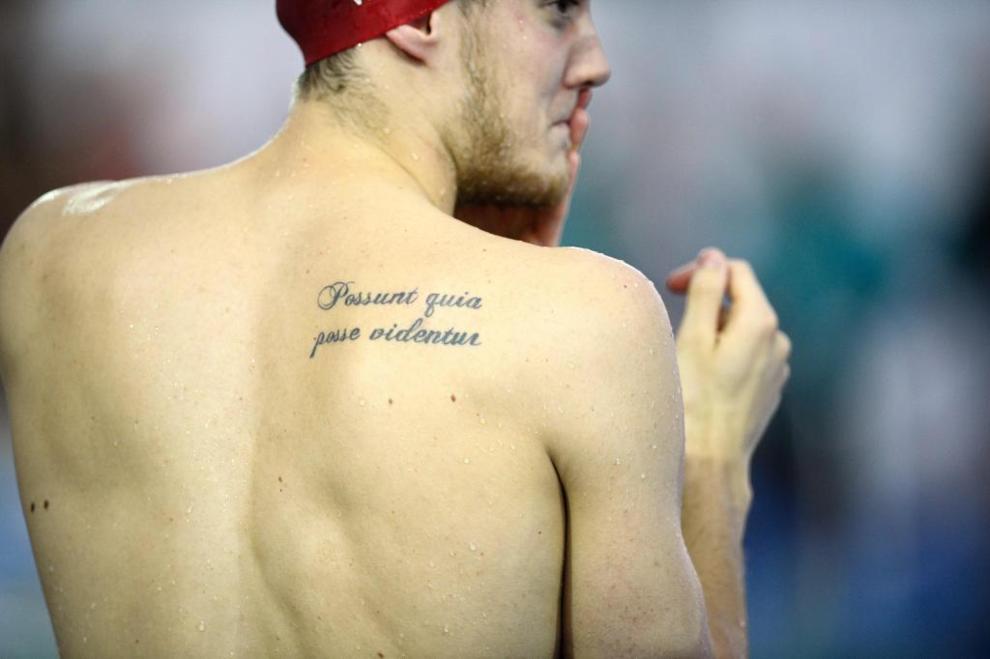

The Latin title of the work, POSSUNT QUIA POSSE VIDENTUR, translates to “They can because they believe” an affirmation of self-determination and strength of will, attributed to the — disputedly queer — ancient Roman poet Virgil. The quote is strikingly optimistic for a game as incomprehensible as pinball but obviously there are deeper implications. The self-efficacy of the maxim is ironic as the three men have been admired, and here recreated, by audiences not likely considered during the development of gay male porn.

Like the physicality of Canova’s white marble, Fiber artist, Piñeres has created a sensual and textural form of homoerotica. Unlike marble, the textile medium lends POSSUNT QUIA POSSE VIDENTUR a sense of domesticity. Ultimately, the queer spectacle is downplayed by Piñeres’ technique of stitched needlepoint.

Piñeres’ work provokes the questions: “Who is sex for?” “When is it appropriate?” “When is it deviant?” and “Who is allowed to participate?” If Pornhub has proven anything, it’s that there are no right answers.

Latest Work

Piñeres has departed from the pictorial representation of gay men in her newest series Primordial Chaos, in which nude females wrestle amid a cacophony of shapes and colors.

The women are camouflaged in the patterns, with their skin the same colors as the abstract background. The work speaks to mankind’s origin and nature. The women reference the ancestral mother Gaea, of Greek mythology, who gave birth to all life.

The series title, Primordial Chaos, recalls the creation of the universe and the Biblical quote from Genesis, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” In fact, humans are the very same matter as stardust.

Primordial Chaos is also inspired by Netflix’s GLOW, a fictionalized series about a real 1980s TV broadcast titled Gorgeous Ladies Of Wrestling. The show is a complex portrayal that has been both praised for its feminism and indicted for its objectification of women.

About Primordial Chaos, curator (and drag queen), Michael Anthony Farley writes, “I like the distinct visions of “women’s work” presented by both traditional textile craft and professional wrestling, here gloriously married in technicolor.”

The Walter Maciel Gallery describes the series in this way, “Piñeres’s Primordial Chaos is a masterful articulation of her desire to resolve the conflict within herself and thus the whole. […] Piñeres calls on us to submit to chaos and to discover grace in conflict.”

Maria E. Piñeres continues to defiantly challenge patriarchy and heteronormativity. I’m excited to see what she creates next. Follow her on Instagram!