The Self-Obliteration of Yayoi Kusama

With Louis Vuitton, the world’s most popular artist paints the finishing touches on her legacy.

Cover photo: An animatronic in Yayoi Kusama’s likeness attracts spectators at the Louis Vuitton boutique in Place Vendome, Paris, France (2023). Via Reuters and El Sol de Mexico (color-corrected).

CONTENT WARNING: This article includes mention of nudity and sex.

Intro

“I can’t imagine a life other than being an artist. I used to live in poverty, not even having enough to eat,” says Yayoi Kusama (草間 彌生). This year, the 94-year-old Japanese artist was again the star of the largest collaboration in Louis Vuitton’s venerated history.

No one is more deserving of the attention. Emerging as one of the first internationally-famous artists outside Euro-America after World War II, Kusama has risen to become “the world’s top-selling living female artist” and “world’s most popular artist”.

Now with Louis Vuitton it seems Kusama is painting the finishing touches on her legacy. “We have never done anything like this before, working over all product categories at the maison,” explained Delphine Arnault, former executive vice president of Louis Vuitton. The collection features over 450 items, tracing Kusama’s entire career through flowers, faces, pumpkins, and — of course — dots. I was eager to have a piece of her world for myself!

Let’s take a look back at one of the year’s biggest art/fashion moments. How did Kusama evolve from her humble roots as an avant-garde radical to mainstream luxury darling? What does this intense commercialism mean for her reputation? Did she achieve fame, or simply let it swallow her alive?

Fashion

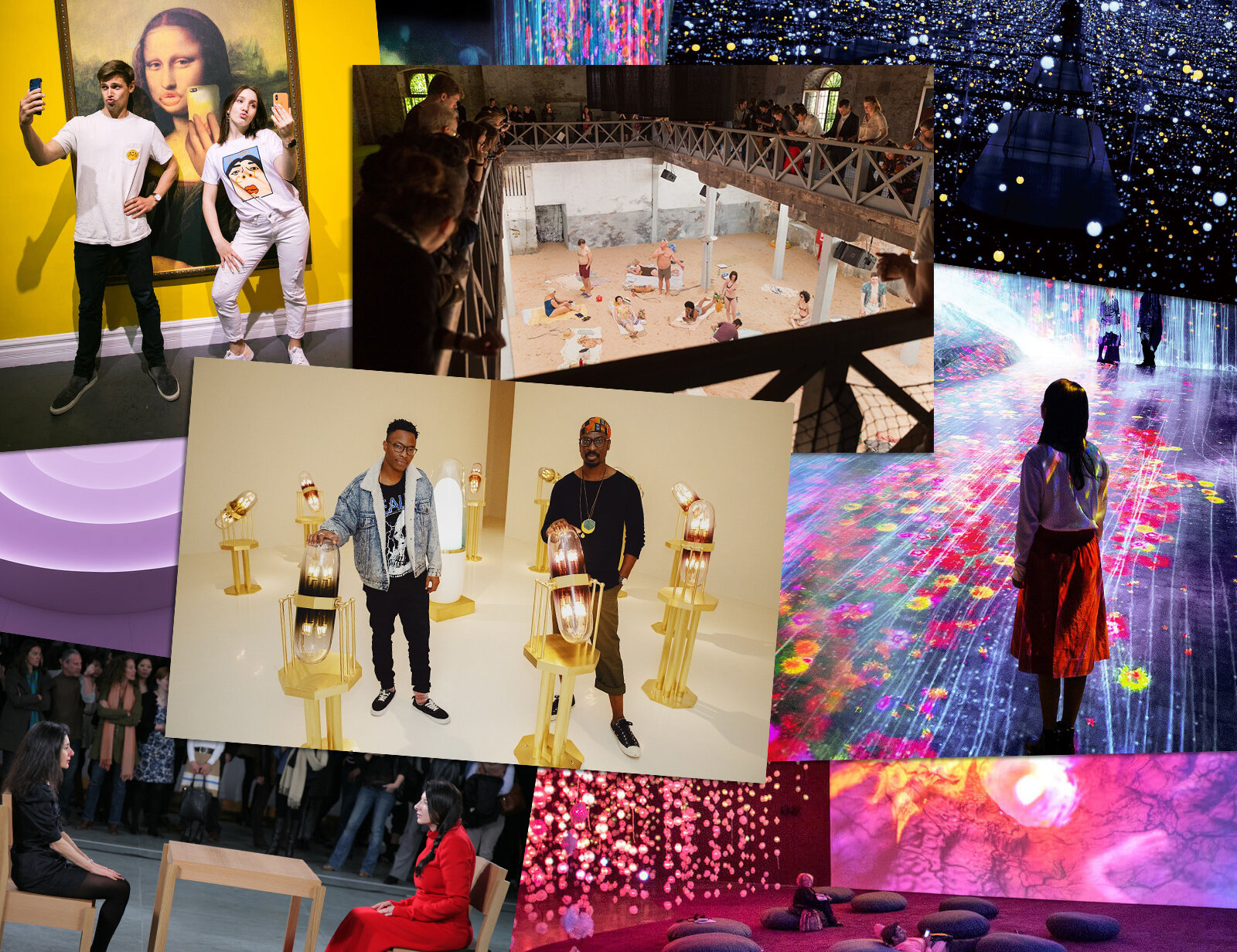

Associated with surrealism, automatism, pointillism, minimalism, pop, and psychedelia, Kusama is undefinable. Her work spans painting, collage, sculpture, performance, installation, film, poetry, novels, music, and fashion.

In the 1960s, Kusama started her own clothing line, selling erotic pieces with strategically placed holes for breasts and genitals, very different from the haute couture of Louis Vuitton. She staged naked “orgies” across New York in celebration of love and freedom.

“For me, all mediums of expression are essentially the same, and all are important,” Kusama explains, “Like art, beautiful fashion can bring inspiration, joy, and help us to fight boldly against life.”

Healing

Throughout her prolific life, Kusama had one overarching goal: healing. Kusama treated art as therapy for trauma and activism against all the world’s ills, fighting against sex, consumerism, and violence.

Born in 1929 to a wealthy family of gardeners in the castle town of Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, Kusama experienced a difficult childhood marred by her father’s constant infidelity, her mother’s disapproval of her creative pursuits, and the destruction of World War II.

“There were wars when I was a child, and even now in the world there is still terrorism, war, so much hatred and scars against humanity,” reflected Kusama. She says, “I create art for the healing of all mankind.”

Self-Obliteration

Kusama’s most-enduring idea is “self-obliteration” (自己消滅), an artistic process that enables the dissolution of personhood to achieve unity with the universe. Inspired by depersonalization, Kusama transmuted her wish to disappear into this suicide-adjacent desire for self-obliteration.

As early as the age of ten, Kusama’s mental illness manifested in visual and auditory hallucinations. In a formative experience, Kusama recalls, “One day I was looking at the red flower patterns of the tablecloth on a table, and when I looked up I saw the same pattern covering the ceiling, the windows, and the walls, and finally all over the room, my body and the universe. I felt as if I had begun to self-obliterate, to revolve in the infinity of endless time and the absoluteness of space, and be reduced to nothingness.”

Kusama’s art became defined by obsessive repetition. She anointed herself the “High Priestess of Polka Dots,” covering everything she could touch in all-consuming patterns. She painted canvas, herself, strangers, and once — at the music festival Woodstock — a horse.

In 2002, Kusama debuted her first Obliteration Room. The installation begins as a stark white domestic space, but it is slowly consumed in a burst of color by hand-placed stickers given to visitors. In this way, Kusama invites everyone to join her in obliteration. The interactive work has been featured at 20 venues, in 15 different countries, welcoming some 5 million participants.

“Kusama wants to become the most visible woman in the world by making herself disappear,” wrote critic Andrew Solomon in 1997. Communications professor Erin Stapleton accuses Kusama of “a lifelong performance of suicide, exhaustively commodified.”

While Kusama’s art could be dismissed as spectacle, it offers a glimpse of divinity. To be one with the universe, is to feel total peace, a sense of belonging and kinship not only with our fellow beings, but all the atoms composing and surrounding us.

Kusama’s obliteration recalls the Biblical idea that, “you are dust, and to dust you shall return,” or the belief that “We are a way for the cosmos to know itself,” as expressed by the physicist Carl Sagan.

By definition, Kusama’s idea of dotted obliteration is flexible and infinitely-scalable. It also makes for efficient branding. For items in the new collection, Louis Vuitton craftsmen developed a new technique combining serigraphy (screen-printing) and embossing to reproduce the wet impression of the artist’s dotted brushstrokes.

Louis Vuitton also partnered with the social media group Snap to create a series of augmented reality (AR) camera lenses, for users to virtually decorate their surroundings. “We wanted to make something on a huge scale, that also has a huge meaning: painting the world’s biggest landmarks and monuments,” says Geoffrey Perez, Snap senior manager.

Kusama unapologetically chased fame while maintaining her own integrity and originality. She dressed in traditional kimono, staged orgies, and she even publicly offered to have sex with Present Nixon in exchange for an end to the Vietnam War.

“Publicity is critical to my work because it offers the best way of communicating with large numbers of people,” Kusama explained, arguing that her rapturous desire for fame was ultimately in service to humanity. “[T]he public was fascinated by my activities and movements,” observed Kusama, which, she argues, “proved how starved they were for Love and Peace.”

Kusama was castigated for her “lust for publicity” while the men around her were lauded for the blatant appropriation of her ideas. Her genuine inventiveness was plagiarized by Andy Warhol, Lucas Samaras, and Claes Oldenburg; nevertheless she continued to create art while fearing herself doomed to obscurity.

In 2018, she admitted, “Long ago, I decided that all I could do was express my thoughts through my art and that I would continue to do this until I died, even if no one was ever to see my work.”

Otherness

With massive installations in New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo, Louis Vuitton drowned the Northern Hemisphere in a “dizzying flood of polka dots” and “Kusama’s body has joined the dots in becoming just another pattern: she is replicated again and again,” wrote artist Isabella Segalovich.

Kusama’s likeness appeared on billboards, apps, and a small army of hyperreal animatronics, causing viral sensation. In London, a 15 meter (49 feet) tall sculpture of Kusama towered over Harrods, and in Paris, an inflatable likeness loomed over a Louis Vuitton boutique. These portrayals cast Kusama as other-worldly and alien.

The colossal installations have been compared to popular anime Attack on Titan (進撃の巨人). Culture critic Thu-Huong Ha complained, “they’re not elegant.” Instead, it’s kitsch and it’s camp, like classic Kusama. Ha concludes, “this is a natural evolution for her as she just gets bigger and bigger, physically bigger, just — department-store-sized Kusama.”

Journalist Hindley Wang argued that Louis Vuitton has literally objectified Kusama to become “the stereotypical mute and absent Asian woman” as she’s displayed alongside the maison’s consumer products with vacant expression.

The conversation is sensitive as attacks against Asians skyrocketed amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic; in the United States alone a total of 10,000 hate crimes were reported throughout 2020 and 2021.

The nonagenarian has herself grown quiet, severely limiting interviews and public appearances. Though “very intelligent and quick-witted,” an anonymous friend argues, “Kusama is often misunderstood because of her illness.”

Globalization

Exploring anxieties of an Asian-dominated future, “techno-orientalism” originated in the 1970s, prompted by Japan’s postwar economic boom, a rise so great it was considered nothing short of a miracle.

“[Americans and Europeans] feared they would be outpaced in both technological and political clout, with Asian nations flipping the table and turning the previously colonized into the colonizers,” writes George Yang for Wired magazine.

This science-fiction genre is distilled into the indelible image of a Japanese geisha advertising birth-control pills in the 1982 cult classic Blade Runner. The film’s cyberpunk aesthetic was heavily influenced by urban Tokyo. Director Ridley Scott depicts a gloomy vision of a future inundated by mass-media and technology.

The film’s world is dominated by Eldon Tyrell, the eponymous head of Tyrell Corporation, responsible for engineering Replicants, artificial humanoids built to serve as slave labor. His motivation is explicit: “Commerce is our goal here at Tyrell.” The corporate behemoth is a symbol of monopoly capitalism, not entirely unlike the French luxury conglomerate LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy), which owns some 70 brands, including Louis Vuitton.

Like the Tyrell Corporation, LVMH is a monopolizing cultural force, collecting top talent in service of shareholders. With an unfathomable net worth of $200 billion, the wealth of the group’s founder and CEO, Bernard Arnault, has surpassed even that of American tech-lords.

After Kusama’s first collection with Louis Vuitton, Javier Pes and Emily Sharpe of The Art Newspaper, called her the “poster girl for the globalisation of contemporary art.” While this second collaboration may lack novelty, it’s no surprise that Louis Vuitton partnered with Kusama once again.

Arnault judges creative merit by sales figures. While artists are generally shy about commercial ambition, “true artists,” argues Bernault, “want people to wear their dresses, or spray their perfume, or carry the luggage they have designed.”

Amidst growing fears of automation and AI, it seems especially tasteless to have a Kusama-bot slavishly pantomime painting in service to the richest man alive. When I walked past Louis Vuitton’s Osaka flagship boutique at midnight, I was disturbed to find Kusama still flailing about in the darkened storefront.

Commodification

In 1966, Kusama debuted her work Narcissus Garden outside the 33rd Venice Biennale, considered the ‘art world Olympics.’ In protest of art’s commodification, she sold mirror balls for 1,200 lira or $2 each. Now, Louis Vuitton merchandise inspired by her protest retails for over $700.

Stickers for the social media app Line depict Kusama as Louis Vuitton’s mascot Vivienne (2023). Via Line.

Though largely divorced from success in her secluded hospital residence, Kusama’s unprecedented popularity — and specifically her success in the commercial world of luxury — has raised questions of ‘selling out.’

Upon the artist’s first Louis Vuitton collection, blogger Richard Metzger wrote, “Self-Obliteration For Very Rich People: Yayoi Kusama for Louis Vuitton?” Kusama had once argued, “I am against that materialistic culture which considers art as something to be consumed, a commodity.”

“Long gone are the days back in the 1960s and 70s when Kusama was producing pioneering work,” laments writer Dr. Victoria Powell. Kusama has achieved the immortality she has long craved, by becoming the commodity she once protested, self-obliterating into a global luxury-goods brand.

In January, LVMH reported an annual growth of 17% in the last quarter of 2022. After President Macron had proposed raising the French retirement age from 62 to 64, local activists stormed LVMH headquarters in opposition to the national pension reform. Union leader Fabien Villedieu argued, “If Macron wants to find money to finance the pension system, he should come here to find it.”

Conclusion

I first fell in love with Kusama in 2017, after visiting her monumental retrospective in Seattle. I found her work to be nothing short of a revelation, the combination of her simplicity and grand scope was mesmerizing. I have since chased her work around the world, from New York and London, to Matsumoto, Naoshima, and Tokyo.

When I had an opportunity to meet Takashi Murakami in 2018, I made a point to tell him that he was my favorite artist only after Yayoi Kusama (which I now realize was not particularly polite).

I first visited the Kusama Museum in Shinjuku last year. I had a fantasy that she would happen to be there, surveying her art, ready to greet me in her iconic red wig. “Hajimemashite. It’s such a pleasure to meet you,” I would tell her while performing a deep bow. “You have shown me beauty and given me strength.”

While Kusama is often framed as a suffering artist at the mercy of mental illness, the idea of her as a mere vessel for uncontrollable urges minimizes her agency and neglects her talent. She simply would not have been able to achieve her success without enormous focus and discipline. Kusama was relentless in her pursuit of success, while possessing a moral clarity and sense of self.

In January, Kusama made a rare public appearance to celebrate the new collection. She said, “I wish everyone happiness.” Perhaps there is a limit to what art by itself can accomplish, but I will remain forever grateful to Kusama.