The Invisible Labor of Food by Annibale Carracci

Carracci introduces dignity to working people while removing the sight of their own labor.

Cover photo: The Butcher’s Shop, oil on canvas, by Annibale Carracci (circa 1582). Via Wikimedia.

The Art of Labor

At the height of the Industrial Revolution in the United States, American workers — including children — suffered twelve hour work days and seven day work weeks. Labor Day originated in 1882 as an annual mass rally in New York organized by socialists and leftist organizations to demand shorter hours, higher pay, safer working conditions, and a labor holiday. President Grover Cleveland would declare Labor Day a federal holiday in 1894.

COVID-19 has revealed who are the essential workers and who performs the unnecessary “bullshit jobs”. This once-in-a-century pandemic has also demonstrated the global interdependency of resources, labor, and supply chains — what we commonly refer to as globalization.

Millions of Americans have lost their jobs, and likely their healthcare. This has inspired me to create a new series on the art of labor through the centuries, with a focus on how work has been valued and represented.

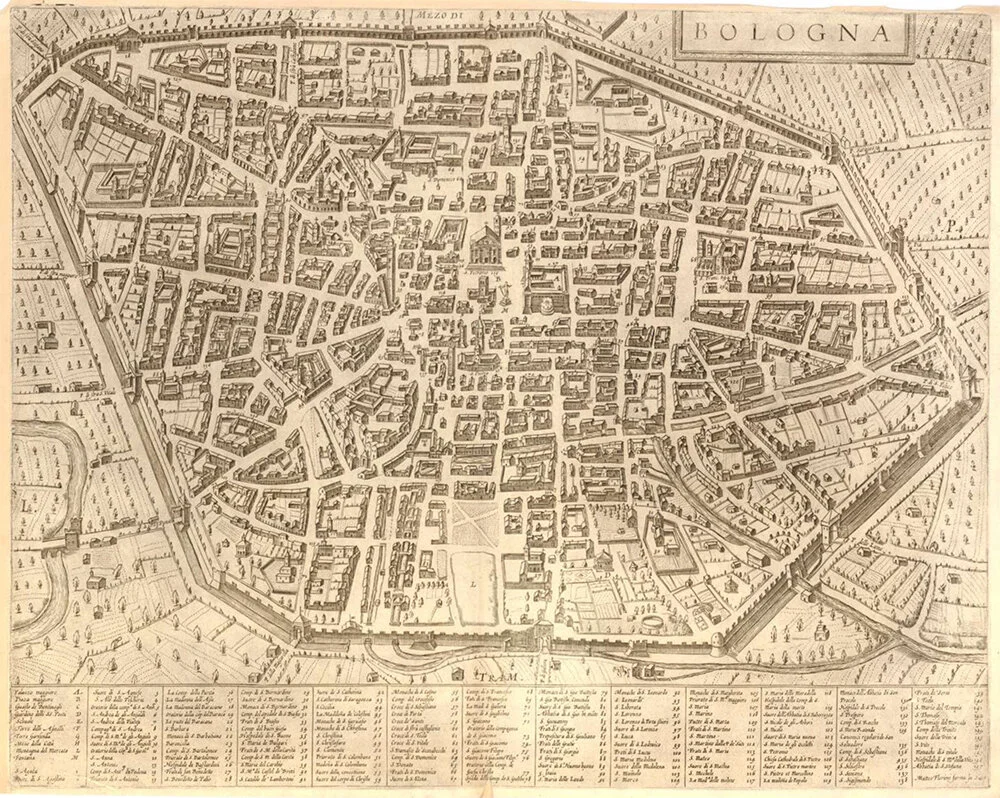

“By the second half of the sixteenth century Bologna had a population of approaching 60,000, an established religious community and, partly due to having one of the largest Universities in Europe, an eclectic range of intellectual and scholarly inhabitants,” note Paul Freathy and Iris Thomas of the Institute for Retail Studies.

“It pleased God that in the city of Bologna, the mistress of sciences and studies, a most noble mind was forged and through it the declining and extinguished art was reforged,” observed the 17th century biographer Giovanni Pietro Bellori. “He was that Annibale Carracci, […] coupling two things rarely conceded to man: nature and supreme excellence.”

Annibale Carracci was born in 1560 to a talented family. He learned painting from his cousin Ludovico and printmaking from his brother Agostino. Likely enabled by Agostino’s financial success in printing, the three Carracci founded an artist academy in 1582 to rival the prevailing idealistic and artificial Mannerist style.

“The Carracci Academy was founded in a cultural climate characterized […] by an atmosphere of scientific discovery, observation of nature, and artistic reform,” writes art scholar Sarah Beth Wilson. Drawing from perspective, light, and anatomy, the three Carracci sought to develop an artistic style that was perfectly mimetic.

18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant would later argue, “Thus the purposiveness in the product of beautiful art, although it is certainly intentional, must nevertheless not seem intentional; i.e., beautiful art must be regarded as nature, although of course one is aware of it as art.”

Artistic Reform

“The reemergence of the merchant classes after the economic stagnation of the early 14th century and the devastating effects of the Black Death saw a growth in consumerism and the large scale production of artistic works,” write Freathy and Thomas. In a departure from religious iconography, there was ”a growing interest in “genre” art with images of street scenes, markets, bars and taverns proving particularly popular.”

According to European art curator C. D. Dickerson III of the Kimbell Art Museum, Bartolomeo Passarotti was one of the first Italian artists to depict the profession of butchery. Passerotti’s rendition of a butcher’s shop is a staged, brutish portrayal of misshapen caricatures, depicted in garish colors. Dickerson argues that Passarotti was likely influenced by contemporary theater to accomplish the comedic rendition of The Butcher’s Shop.

In his 2010 book, Raw Painting, Dickerson writes, “The audience was a high one, and the portrayals were meant to emphasize the stereotypical vulgarity of social inferiors. The viewer was invited not to sympathize with low people but to laugh at them and, through laughter, to take comfort in the fact that he or she was naturally superior.”

Passarotti suggests that the lower class is as crude and simple as the foods they consume. According to Freathy and Thomas, such physical deformities “reflected the view that manual labour distorted the body over time”.

In contrast to his teacher, Carracci’s first version of The Butcher’s Shop — completed around 1582 — was an early synthesis of the concepts of realism and effortlessness. His brushwork is fast and loose, creating a sense of spontaneity. The colors are earthy and muted. His butchers appear frozen in time.

Butchery is a profession that Annibale Carracci was intimately familiar with and sympathetic of, as his uncle and cousins were in the trade. “In the world he experienced, the sons of tailors and butchers could and did become professional artists,” notes American historian Lester Little. Annibale’s cousin Ludovico would have undoubtedly become a butcher — he was enrolled at the butcher’s guild at the age of five — had he not discovered a love of art.

In the late 1580s or early 1590s, Annibale Carracci illustrated Le Arti di Bologna, a series of seventy-five print etchings of laborers in Bologna. While the series was not published until after his death, art historian Sheila McTighe posits the series was created as a “consciously counter-hegemonic” force that would have contradicted the “supposed deformity of manual laborers”. As writes Little, Carracci instead gives “his street people the posture and poses that artists routinely used to depict nobles.”

Food and Class Hierarchy

Today, Bologna is known as a mecca of Italian cuisine. For The New York Times, author Herbert Lottman wrote, “It must be admitted that the cuisine of Emilia‐Romagna, and particularly that of Bologna, is a hymn to the taste, a triumph of the palate, and a sublimation of the best that man has been able to achieve in the field of gastronomy.”

This exalted gastronomy has origins in a strict class hierarchy “that included a distinction between intellectual and manual labour,” as write Freathy and Thomas. Scholar Laura Giannetti explains, “Fifteenth-century regimens, mainly based on ancient physiological theory, presented an essential dichotomy between workers and leisured classes.”

It was believed that delicate foods were destined for the sensitive brains of a sedentary nobility, while rough foods provided the energy needed for the manual labor performed by lower classes. In his 1583 treatise on diet, Bolognese physician Baldassare Pisanelli, wrote, “Partridges are only unhealthy for country people”.

This distinction traces back to Aristotle’s theory of the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. Foods that were found in the earth or considered hard to digest were deemed appropriate for the lower classes, such as vegetables, beans, pork, and mutton. Foods that were delicate or found in the water and air were reserved for upper classes, including fruit, fish, chickens, and veal.

In his 1999 book Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present, Professor Albert Sonnenfeld writes, “It seemed self-evident that God had created the world as well as the laws that governed human society, both being structured by a vertical and hierarchical principle.”

Invisible and Aesthetic Labor

Carracci’s early rendition of The Butcher’s Shop is notable not only for what it depicts, but — more importantly — what it omits: a near total absence of labor. Like his teacher, Carracci hides the work of the butchers, just hinting at it; the man on the left handles his knife, while the man on the right is hanging or removing the slab of meat.

Referencing Carracci’s later version (which resides today in Oxford), art critic Michael Glover writes for the Independent, “It lacks fleshiness; it lacks the texture, the mess, the blood.” The very concept of death is obscured. The artist only permits the viewer to bear witness to already dry carcasses, fresh blades, and a spotless floor. Scholar Paloma Stasia Campbell argues that Carracci has captured “the severance of labour from the labouring body.”

“Both the act of slaughter and the spilling of blood have been rendered invisible,” observes Campbell. Professors Marion Crain, Winifred Poster, Miriam Cherry, write in their 2016 book Invisible Labor: Hidden Work in the Contemporary World, “labor may be hidden from public view when it is separated architecturally, institutionally, or socially.”

The manual labor of killing and preparing animals for consumption has instead been replaced by an aesthetic labor, which is — in simplest terms — the curation and styling of the body within the context of work.

The theory of aesthetic labor was developed by researchers Chris Warhurst, Dennis Nickson, and Anne Witz, now referred to as the Strathclyde group. According to the group, “aesthetic labourers are engaged in a staged performance that depends upon the deployment not only of technical skills and emotion work skills, but also of specific modes of embodiment or ‘styles of the flesh’.”

As write Freathy and Thomas, tradesmen struggled against “the association of butchery with contagion and disease.” In addition to their offerings of meat, the two butchers sell the appearance of cleanliness and effortlessness. The uniform of crisp white linen aprons denotes the shop as perfectly sanitary. Butchers would likely have kept multiple pairs to ensure complete freshness in front of customers.

Campbell explains, “The painting was produced at a moment when the butchery profession in Bologna was becoming more regulated in terms of where animals were slaughtered and how meat was sold.” Due to concerns of pollution and safety, the killing of animals was moved from outside, in busy city streets, to the private confines of the butcher shop.

“By the time a cut of meat reached the dining table, it had traveled a route that involved herders and livestock sellers as well as the butchers themselves,” writes Dickerson. This chain of laborers is “out of sight, out of mind”.

“As the taste of the porridge does not tell you who grew the oats, no more does this simple process tell you of itself what are the social conditions under which it is taking place,” observed Karl Marx in his 1867 book Capital, Volume I.

The theory of aesthetic labor relates to the Italian concept of sprezzatura — loosely translating to “nonchalance” or “disdain” — which was coined by Baldassare Castiglione in his 1528 novel Il Cortegiano. Castiglione describes sprezzatura as a kind of practiced effortlessness, or, in his own words, “an art which does not seem to be an art.”

As writes John David Rhodes in his article Belabored: Style as Work, “Labor disappears into a seamless social performance, sublimated away by its own invisible efforts.” Explains author Brand Miner, “Implicit in sprezzatura is not only an effortless elegance but also a strenuous self-control.” The styles of the three Carracci, as well as that of their pupils, were so similar that they would regularly share art commissions. Some of the work on the trio’s frescos has been deemed indistinguishable.

Dickerson argues that, despite its hurried appearance, Carracci almost certainly created The Butcher’s Shop in his studio as there was no established tradition of plein-air painting in Italy. Nevertheless, Dickerson commends that the work is “utterly revolutionary” in Carracci’s search “for new ways to simulate in painting the visceral experience of looking at the world.”

Today

Industrial factory farming, slaughter houses, and complex supply chains have decreased the visibility of workers, furthering the separation between work and product. In Italy today, there live some tens of thousands of undocumented migrants. Their status makes them vulnerable to increased exploitation, such as enslavement and sexual abuse.

It is impossible to fully comprehend the working conditions behind the plastic-wrapped products purchased in supermarkets. Across the globe, there is a growing interest in local, organic, and ethically-sourced foods.

In a 2011 episode of the comedy sketch show Portlandia, two restaurant guests leave without eating after asking their waiter about the chicken they are about to eat. Asks Carrie Brownstein’s character, “Who are these people raising Colin?”

Aboubakar Soumahoro, an African-Italian trade unionist who is the subject of the 2020 short documentary The Invisibles by Carola Mamberto and Diana Ferrero, explains, “We are a union of invisibles who demand to be seen and to pursue our happiness.”