Remembering Fernando Botero

Through exaggerated volume, Botero made monuments to humanity.

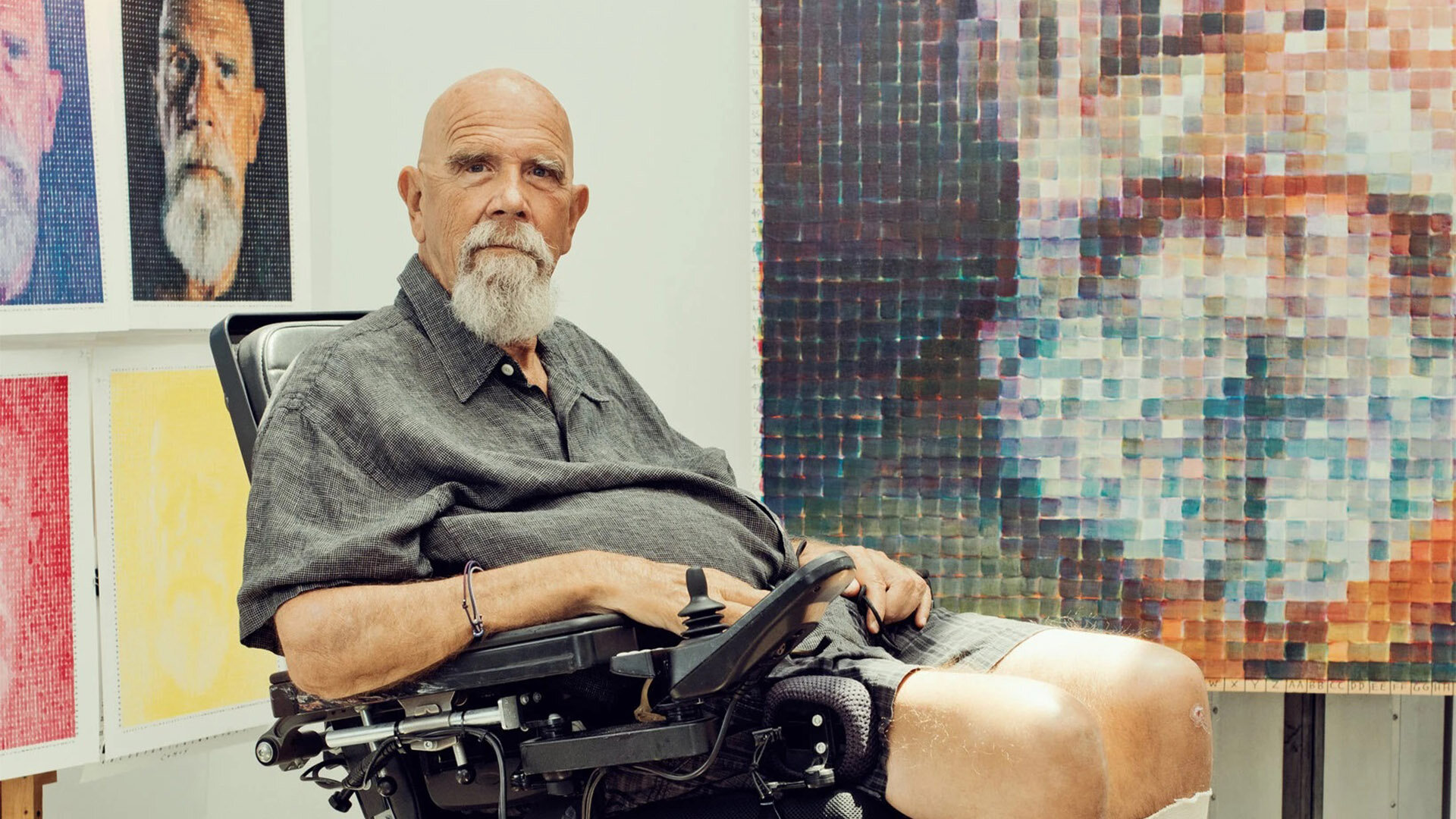

Cover photo: Fernando Botero at his studio in Monte Carlo, Monaco (2012). Via Getty and Vogue (cropped).

Intro

On Friday, September 15th, the Columbian artist Fernando Botero passed away at the age of 91 due to pneumonia complications. His prolific career spanned six decades.

President Gustavo Petro mourned, “The painter of our traditions and our defects, the painter of our virtues has died.”

Recognized for his signature style of playful proportions — called Boterismo — Botero was considered Latin America’s most famous artist, with his work displayed around the globe. Though often dismissed by critics, Botero was widely beloved for his nostalgic, populist images of supersized people.

Boterismo

Botero fought against the prevailing “dictatorship of abstract art” with his own brand of iconoclasm. He made the serious silly, and the silly serious. Botero gave the same fleshy gravity to every subject, including matadors, ballerinas, presidents, and Jesus Christ.

His creations were described as rotund, massive, bloated, puffy, bodacious, hefty, robust, voluptuous, bulbous, round, inflated, portly, swollen, curvaceous, and plump, but there was one word he detested: fat.

Botero was not interested in fatness per se; inspired by artists of the Italian Quattrocento (1400s), Botero found obsession strictly in the “miracle” of volume. He employed extreme physicality “to celebrate existence,” and to render life full and sensual.

“My fundamental interest,” Botero realized, “is to paint an oranger orange which is all oranges — the summary of all of them.”

History

Botero began work as a newspaper illustrator after he abandoned his childhood dream of bullfighting. At age 20 he left to Spain, studying painting at Madrid’s Academia de San Fernando.

In Europe, Botero began to imitate the Old Masters. These recreations were part homage, part rejection. “I am saying that I am equal,” he declared, whilst searching for his own authenticity.

At just 29 years old, he rose to fame with a bizarre rendition of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. “Is Botero going to infantilize the whole history of art?” a German critic worried, but Botero proved himself able to face difficult subjects, local and contemporary. He depicted massacres, military juntas, the death of drug lords, and the abuse of prisoners.

Interpretation

Botero was difficult to define. Critics were quick to associate him with the magical realism of celebrated author and fellow Columbian Gabriel García Márquez. Botero vehemently denied the comparison: “I do not do magical realism. What I do is improbable, but not impossible.”

Others interpreted humble Botero’s girthy figures as critiques of wealth, indulgence, and consumerism. Novelist and critic Erica Jong proclaimed them “a record of the brutality of the haves against the have-nots.”

Still more critics derided his work as kitsch, unfocused parody, reliant on fatness as humor. Rosalind Krauss asserted, “he’s speaking down to the viewer” with characters recalling “the Pillsbury Dough-Boy.”

“For centuries there was this kind of form,” argued Botero, citing pre-Columbian art, “now all of a sudden it is necessarily a satire.” Whether through color, shape, or line, Botero defended, “Art is always an exaggeration.”

Body

Amidst prevailing western standards of thinness, Botero developed his signature style in 1957, a full decade prior to the origins of the body positivity movement. Still, I struggle to deem Botero an activist for fat acceptance.

Notably, neither Botero nor any of his three wives could be described as large. “In the very beginning, some of my paintings were done with a satirical idea,” Botero admitted, but his unwavering commitment to Boterismo evolved the style from mere gimmick into a unified vision.

I was fortunate to see Botero’s retrospective Magic in Full Form in Nagoya last year. His work is inherently joyful. Many Japanese visitors even found it comical, suppressing soft laughter. Looking back upon the show, I was surprised to find his subjects expressionless. Is it only their size that elicits comparison to jolly ol’ Saint Nick?

Late curator Frank Wagner described Boterismo as a rejection of “hostility toward the body” and Botero himself acknowledged it as a counter-cultural force. “I can’t help it,” he said, “[that the] general idea of beauty is that women should be thin”.

As someone who has consistently struggled with weight I found the collection revelatory, almost therapeutic. Despite their hefty size, Botero’s characters don’t feel like caricature. His figures are not grotesque, not terrifying, simply large. They’re treated gently, with empathy.

Botero’s ballerinas possess grace, his musicians a sense of stature, and prisoners dignity. His exaggerated proportions make monuments of everyday people. It’s as if Botero magnified humanity itself.

Legacy

Man on a Horse (Hombre a caballo), 1999, bronze, by Fernando Botero, on view in New York City, New York, United States (2016). Via Christie’s Auction House (cropped).

Despite unflattering critical reception, Botero proved an auction favorite, with works regularly passing the one million dollar mark. “He is a market and a category outside of any other,” explains Kristen France, a vice president at Christie’s. Just last year, Botero’s Man on a Horse sold for $4.3 million, breaking his own record for the most expensive work by a living Latin American artist.

In the year 2000, Botero established Bogotá’s Botero Museum with his personal art collection, and he donated an additional 23 sculptures to his hometown of Medellín to create Botero Plaza.

Though Botero laid the foundation for Columbia to become a global art hub, his outsized reputation proved a double-edged sword, with his enlarged figures overshadowing fledgling creators.

“For years local collectors were only interested in Botero’s work,” lamented conceptual artist Miguel Ángel Rojas. Now, there is a group of artists ready to step into the spotlight.

Botero leaves behind an enormous legacy. He challenged the authority of colonialism, nationalism, and beauty. I hope others will follow in his footsteps. May he rest in peace.