Queer Art Shines at the 58th Venice Biennale

Queer art is the unabashed highlight of the 58th International Art Exhibition.

Cover photo: Image still from the video 00 X, by Shu Lea Cheang (2019). Via the official website of the Taiwanese Pavilion 3X3X6.

WARNING: The following article features and/or discusses graphic nudity, colonization, imprisonment, murder, and sex.

2019’s edition of the Venice Biennale, named May You Live In Interesting Times, is dedicated to examining society and challenging conventions. The title refers to “a phrase of English invention that has long been mistakenly cited as an ancient Chinese curse that invokes periods of uncertainty, crisis and turmoil.” Artists responded to the theme with aplomb, creating works that examine the turbulent history of sexuality, gender, and government sanctioned homophobia. Here is a small selection of my favorite artworks.

Morning Studio by Nicole Eisenman

In the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, visitors will find paintings by French-born American artist Nicole Eisenman including Morning Studio, a depiction of two women laying together on a mattress in a quiet scene of queer domesticity. Eisenman’s style here is delicate and precise, unlike that of her satirical paintings. She treats the subjects with dignity and grace.

This gentle scene does not appear immediately political but, even in 2019, bearing witness to the intimacy of a same-sex couple feels like a radical act. One of the women stares at the viewer, as if daring you to suggest their love is dangerous or perverse.

Swinguerra by Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca

The Brazilian Pavilion, my favorite this year, features a two-channel video installation titled Swinguerra, a choreographed 21 minute performance dedicated to three dance styles in the city of Recife: swingueira, brega funk, and passinho da maloca.

The installation was created by artists Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca in collaboration with predominantly black and non-binary performers from the dance groups Cia. Extremo, Grupo La Màfia and Bonde do Passinho S.A.

The LGBT+ community has been repeatedly demonized by the far-right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro who once said he’d rather have a dead son than a gay one. In April, Bolsonaro declared, “Brazil can’t be a country of the gay world, of gay tourism.”

The name Swinguerra is a play on the dance style swingueira and the Portuguese word for war, referencing the ongoing struggle over queer visibility and autonomy. Ultimately, Swinguerra is a presentation of optimism and resilience in the face of socio-political challenges.

Anthropophagous Indians by Christian Bendayán

The Peruvian Pavilion features the exhibit Trans Tropicalia (Fragments) by Christian Bendayán. Most striking is Anthropophagous Indians, in which Bendayán depicts a group of trans Amazonian women performing a tribal dance in the Peruvian city of Iquitos reclaimed by the jungle. The work is an anachronistic image that draws from the country’s rich and complicated history.

Bendayán extends the concept of transness to the boundaries between people, between nature and urbanism, as well as between history and modernity. He notes, “I am not painting an Amazonian ethnicity, but a group of trans girls making thousands of ethnicities. There is a combination of Huitoto and Bora body paint, and postmodern Shipibo spears. All these elements tell us about the Amazon as pastiche. And all this happens in front of the Casa de Fierro, where the Iquiteña high society met and where the first film was screened in the city, in 1900.”

The artwork’s title is derived from archival postcards which often featured the phrase “Indios Antropófagos” or Man-Eating Indians. Spanish Conquistadors argued that practices of cannibalism and homosexuality justified colonialism. About the native people, Spanish royal chronicler Fernández de Oviedo wrote, “It is not without cause that God permits them to be destroyed.”

Body En Thrall by Martine Gutierrez

Work by trans Latinx American artist Martine Gutierrez can be found in both the Central Pavilion in the Giardini and the Arsenale. Her photographs are reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s cinematic self-portraits which famously explored gender and identity.

Gutierrez acts in full autonomy, as model, stylist, and photographer. The photographs are mesmerizing in how they contrast both her control and vulnerability. In her Body En Thrall series, Gutierrez combines the surreal with the mundane. In one photo, she wears a bra padded with melons, a visual pun, which draws upon the body dysmorphia that women — especially transwomen — often feel.

In another scene, Gutierrez floats in a pool while she stares upward at a mysterious man, his shoes just inches away from her face. Gutierrez draws upon the fatal dynamics of power, patriarchy, and the male gaze. Trans women of color have been increasingly terrorized in the United States. So far this year, at least 16 transgender people have been killed.

Pathos and the twilight of the idle by Michael Armitage

Inside the Arsenale, there is a series of vivid paintings by London-based Kenyan artist Michael Armitage. The Promised Land is inspired by opposition political rallies in Nairobi leading up to the 2017 Kenyan elections.

In the artwork Pathos and the twilight of the idle Armitage captures a grotesque fervor in the body politic. Figures appear to scream in anger and desperation. A women levitates in the center of the composition, armed with stones mounted in slings. About the rallies, Armitage recalls, “There was so much going on visually that I started to think about fanaticism and how similar politics and protest can look like around the world.”

While not as explicitly queer as Armitage’s other works, Pathos and the twilight of the idle draws upon universal socio-political concepts of power and visibility that affect the LGBT+ community. In Kenya today, homosexuality remains illegal. According to the Kenyan government, 534 people have been arrested for same-sex relationships between 2013 and 2017.

Faniswa, Seapoint, Cape Town by Zanele Muholi

Since 2015, South African non-binary visual activist Zanele Muholi has begun a massive undertaking to create a series of 365 self-portraits. In this series of protest, titled Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness), Muholi employs props and exaggerates their skin tone to reconstruct and define their own image.

In Post-Apartheid South Africa, where same-sex marriage was legalized in 2006, both racism and homophobia continue to exist. “Curative rapes” are common, in which men sexually assault queer women with the supposed goal of converting them into heterosexuals. Taking control of self-representation, Muholi peacefully fights for their right to exist.

Muholi uses photography to empower the LGBT+ community in South Africa. In 2009 Muholi founded Inkanyiso, a media site collective that documents queer life.

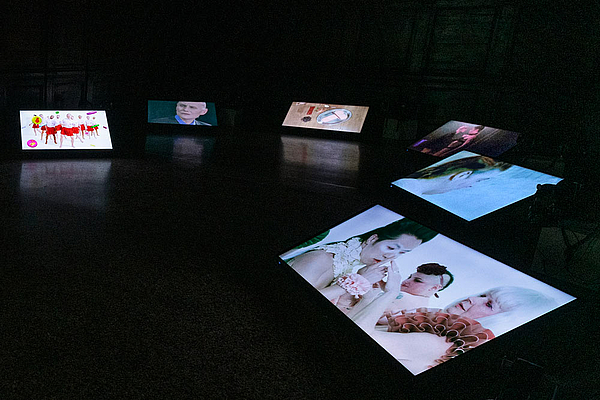

3X3X6 exhibition by Shu Lea Cheang

The Taiwan Pavilion is the one of the best the 58th Biennale has to offer. Artist and filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang has created an unmissable, truly haunting experience. This auxiliary pavilion is set in the Palazzo delle Prigioni which served as the prison for the Doge’s Palace where writer Giacomo Casanova was famously imprisoned in 1755.

Casanova was a famous seducer of women (and occasionally men). He was on the forefront of sexual liberation and one of the earliest adopters of condoms. His actions outraged the Catholic Church and he was arrested by the Venetian Inquisition.

Shu Lea Cheang uses this account as a starting point to explore cases of incarceration due to gender or sexual dissent. The exhibition title, 3X3X6, refers to the modern standardized architecture of industrial prison cells: a three by three square-meter room monitored by six cameras. Shu Lea Cheang has created a total of 10 dramatized short films (not available online) that include tales about author Marquis de Sade and philosopher Michel Foucault in addition to Casanova.

These fears of surveillance and imprisonment are as relevant today. Recently, a psychologist and a computer scientist programmed a machine-learning system to distinguish between straight and gay faces. The Chinese government is currently developing a Social Credit System which combines mass-surveillance with credit scores. Similar systems are being created by Silicon Valley in the United States, in the interest of private companies like insurance firms.

These systems are extrajudicial, lack transparency, and offer the accused no presumption of innocence and little recourse for clearing their name. Paired with deepfake technology, with which videos can be altered through artificial intelligence, such systems may be targeted to punish political opponents and dissidents. Shu Lea Cheang offers a dire warning: surveillance will not make marginalized communities safe.

The 58th Venice Biennale is open until November 24th. Three day tickets for students and/or anyone under the age of 26 are 25 euro ($27). If you have the opportunity, I wholeheartedly encourage you to visit.