Ghibli Park: First Impressions

Studio Ghibli’s highly-anticipated theme park has finally opened.

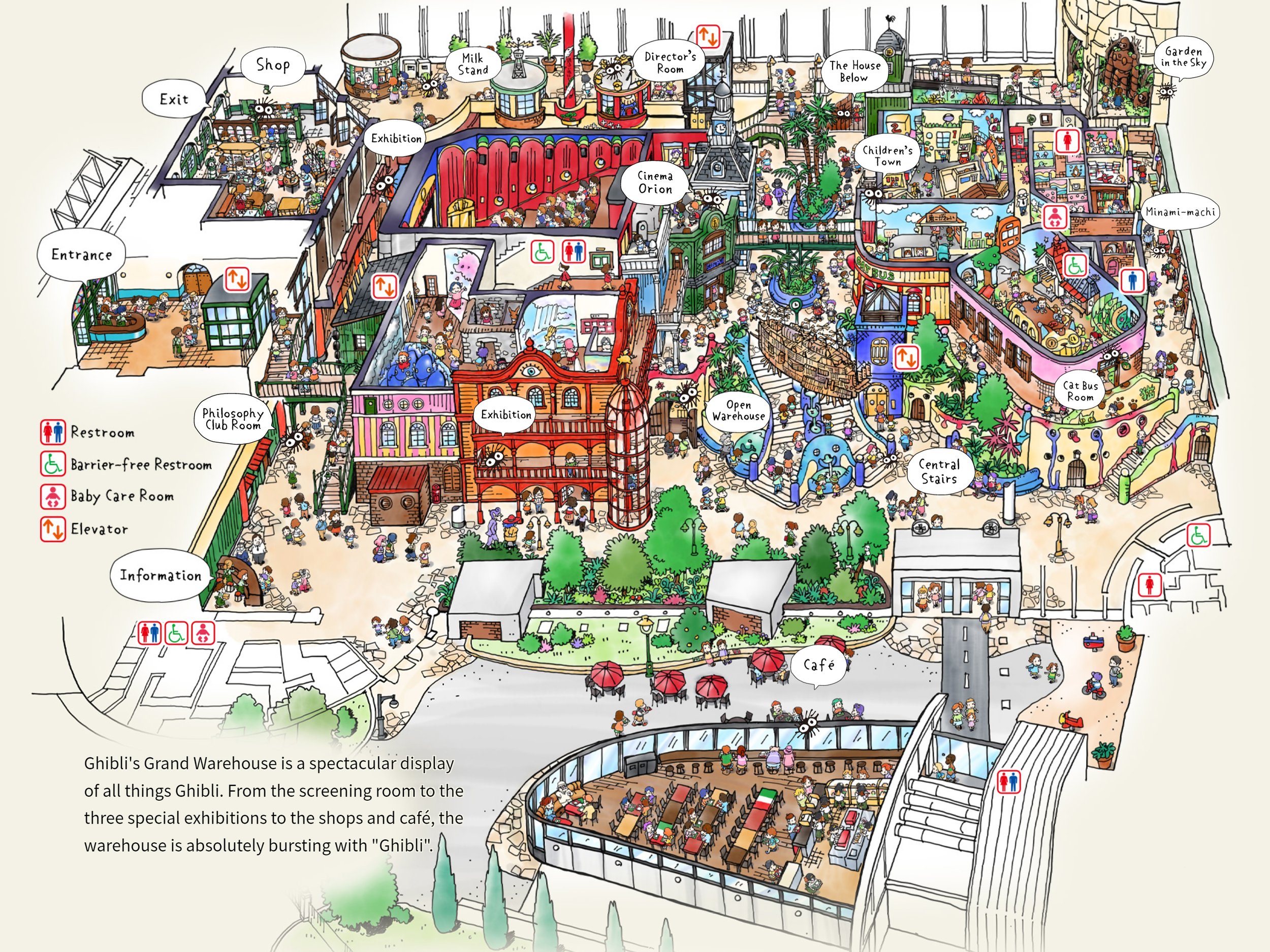

Cover photo: Bathhouse proprietress and witch Yubaba can be found working in the Director’s Room, Ghibli’s Grand Warehouse, Ghibli Park, Nagakute, Aichi Prefecture, Japan (2023). Photo by Danny With Love.

Intro

First announced in 2018, Studio Ghibli’s highly-anticipated theme park has finally opened, located in central Japan’s Aichi Prefecture, outside the city of Nagoya.

Ghibli Park (ジブリパーク) offers fans a new way to experience the whimsical world of the Japanese animation studio internationally beloved for its charming characters, emotional themes, and lush visuals.

Founded in 1985, Studio Ghibli has created 23 feature films, including My Neighbor Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Oscar award-winning Spirited Away.

The park officially opened last November; tickets were first only available to Aichi locals, then expanded to all Japanese residents, with a visitor limit of just 5,000 people per day. I was finally able to reserve a ticket back in December, over three months ago, to visit two of the park’s three open sections: Hill of Youth and Ghibli’s Grand Warehouse.

I first discovered Ghibli back in college, about ten years ago, during my Hot Topic era in which I exclusively wore chino shorts and graphic tees. When I caught a screening of Princess Mononoke at a Dallas anime convention, I was instantly engrossed by the beautiful visuals and heartfelt storytelling, so it’s especially exciting to be one of the first foreigners to visit the park.

The pioneering studio legitimized animation as a mainstream genre, paving the way for box-office hits Your Name (Makoto Shinkai) and Demon Slayer: Mugen Train (Ufotable, Inc). Studio Ghibli has also inspired Western filmmakers Guillermo del Toro, Wes Anderson, and Pixar’s John Lasseter.

Furthermore, Ghibli is the only major studio in the world to retain analog techniques, creating hand-drawn cel-based animation. This laborious craftsmanship imbues the films with a sense of human touch and warmth. Argues lead animator Hayao Miyazaki (宮崎 駿), “I believe that the tool of an animator is the pencil.”

Legacy

Rarely do grand openings commemorate endings, but that’s the idea behind the new park, imagined as a living tribute for the 37-year-old studio nearing its finale. Ghibli’s production team had officially shut down in 2013 upon Miyazaki’s latest retirement but he has returned for one more film, How Do You Live?, scheduled for release this year.

“For a long time, there had been talk of creating a Ghibli theme park, as a way of preserving the studio’s works for future generations,” explains Goro Miyazaki (宮崎 吾朗), Hayao's son, who designed both Ghibli Park and Tokyo’s Ghibli Museum, opened in 2001.

Ghibli’s enduring popularity can be attributed to the studio’s rich nostalgia, with a filmography rooted in Japanese history, mythology, and spirituality, mixed with Western stories and aesthetics. On the surface, the studio’s films are coming-of-age fairytales but they often feature deep themes of technology, ecology, and war.

In contrast to the Western three-act structure, dominated by relentless rising action, Ghibli’s loose plotting originates in the Eastern model called kishōtenketsu (起承転結) [“introduction-development-twist-conclusion”]. Ghibli’s meandering tales are often unplanned, evoking a true sense of spontaneity, exploration, and freedom.

“He gives his protagonists the chance to quiet down and contemplate and just be in nature,” notes Jessica Niebel, curator at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, referring to the Japanese concept of ma (間) [“pause”]. Miyazaki explains, “if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension.” Unlike many Western filmmakers, he is unafraid of silence.

Ghibli renders the mudane with divinity and, while fantastical, the films are wholly sincere. Miyazaki declares, “I want to send a message of cheer to all those wandering aimlessly through life.”

Development

Ghibli Park is discreetly tucked away in the Expo 2005 Aichi Commemorative Park in Nagakute — a 45-minute trip from Nagoya Station — where it occupies 7.1 hectares of the 194 hectare site.

The park already featured Satsuki and Mei’s house from My Neighbor Totoro, originally built for the 2005 Expo. Aichi was chosen as the site of the new park for its minimal environmental impact and tourism potential.

Ghibli Park was built with local materials and not a single tree was cut down on site. The entire project was publicly funded by Aichi Prefecture at a cost of 34 billion yen (approx. $231 million) and the park is managed and operated by a joint-venture between Studio Ghibli and local newspaper publisher Chunichi Shimbun (中日新聞) [Central Japan News].

Located in a prefectural park, ticket prices are low. The Hill of Youth and Ghibli’s Grand Warehouse Package costs just 3,500 yen (approx. $27) and tickets for children (ages 4 through 12) are half-price.

The park is expected to welcome 1.8 million visitors a year once all five sections are complete and open, generating an annual economic impact of 48 billion yen (approx. $350 million). The park has already prompted American magazine TIME to call Nagoya one of the World’s Greatest Places in 2023.

Experience

Stepping off Ai-Chikyuhaku-Kinen-Koen Station, I immediately found myself lost. After following the modest crowd, I descended the Castle in the Sky elevator tower. Staff directed me to my first attraction, the Hill of Youth featuring the World Emporium from Whisper of the Heart.

Inside the antique shop, I was astounded by the attention to detail. The building was filled to the brim with genuine treasure: German tins, vintage books, exquisite glassware, an assortment of decorative clocks, and even carousel horses.

As children feverishly opened cabinets in the kitchen, a Ghibli employee invited me to play with an intriguing instrument I had never seen before, a portative organ. It was an unexpected delight, but I was ready for the main attraction, the Grand Warehouse.

I hurried to escape the rain. Inside a former swimming pool, here visitors can spend the day regardless of the weather. Past the gate, I was surprised to find the entrance unceremonious, leading into an awkward alley. I turned the corner to realize the scale of the enormous building, three times larger than the Ghibli Museum in Tokyo. The warehouse includes multiple shops, exhibition spaces, a movie theater, and elaborate sets.

Full list of attractions below:

Movie Set Experience with 14 iconic scenes from 13 films

Two Special Exhibition spaces

Cinema Orion with 170 seats for animated-short screenings

Open Warehouse with production artifacts and exhibit sculptures

Garden in the Sky set (Castle in the Sky)

Philosophy Club Room set (From Up on Poppy Hill)

The House Below and The Little People’s Garden sets (Arrietty)

Director’s Room with Yubaba (Spirited Away)

Children’s Town and Cat Bus (My Neighbor Totoro) playrooms

Minami-machi shopping street with Japanese bookstore, model shop, and candy shop

Warehouse Shop with exclusive merchandise

Transcontinental Flight Café with pizza, sandwiches, and drinks

Milk Stand Siberian (The Wind Rises) serving local milk and cakes

I first walked through the exhibition spaces which included an in-depth look into Ghibli’s memorable meals, featuring food models, elaborate kitchen recreations, and sketches of characters in the act of eating. The space also included a collection of international memorabilia from a variety of films (photography was not allowed in these two exhibitions).

After walking through the labyrinthine exhibits, at around 13:00, I was ready for lunch. I hoped the later hour meant a shorter line for food but it was still a 40 minute wait to order at the Transcontinental Flight Café.

Inspired by the one-handed meals of Ghibli’s many pilot characters, the café only offers sandwiches and pizza, including a miso katsu (pork cutlet with miso sauce) pizza in homage to local Aichi cuisine. Compared to the gorgeous meals on display at the food exhibit, I found the offerings unappetizing, ultimately settling on a guacamole sandwich and a passionfruit soda float.

Rejuvenated, I headed for Cinema Orion, which screens animated-shorts, previously only available for view at the Ghibli Museum. The current movie is The Whale Hunt which follows a group of playing schoolchildren who imagine themselves to be a traveling upon a seaworthy ship, ultimately chasing a jubilant whale.

The film was adorable, but unfortunately — like in much of the exhibition spaces — there was no English, forcing me to glean what I could through my limited Japanese.

Picture Paradise

After the film, I was ready to brave the long line for the main exhibit, officially called “Becoming Characters in Memorable Ghibli Scenes.” Here, visitors can step into 14 iconic movie moments from 13 Ghibli films, including Porco Rosso, Pom Poko, and When Marnie Was There. I waited 45 minutes to enter the permanent exhibition.

The studio is famed for its “immersive realism” as no detail is spared in creating convincing, all-encompassing worlds. It was amusing to watch — and participate in — the photoshoot mad-dash. I realized there was something uniquely bizarre about the urge to flatten ourselves into Ghibli’s two-dimensional universe.

Back in 2020, I noted that a focus on experience would be a continued trend this decade, but in a world where video platform TikTok threatens the dominance of photography-based Instagram, I wonder if these elaborate backdrops are already outdated.

Culture critic Thu-Huong Ha argues that “given the especially opaque ticketing system and the three-hour journey from Tokyo, it’s ultimately quite a lot of effort [to visit Ghibli Park] for some photos and a Kashira [character] plushy.” With low attendance-caps and limited English support, Ghibli Park seems deliberately inaccessible.

Radical

Many visitors will find Ghibli Park utterly confusing. Compared to the sensory-overload of Disneyland or Universal Studios, it’s a site of Zen-like restraint. “There are no big attractions or rides,” the official site warns. There are no animatronics, costumes, or parades either. It’s surprising, notes journalist Sam Anderson, for an animation studio to create “a place so oddly still.”

“Through its design, the park imparts that visitors are the focus, not Totoro, and that is a truly radical idea.”

Surrounded by motionless sets decorating a former municipal swimming pool, I initially found myself disappointed. Would I prefer a park with rides through the Bathhouse from Spirited Away, a carousel of forest creatures, flying races set in virtual reality?

By 16:00, I watched the Central Staircase slowly emptied of visitors as families began to depart. Absent the echo of a soundtrack playing overhead, the warehouse took on a peaceful silence.

Goro Miyazaki argues, “It’s the visitors that create the motion.” He believes no ride can rival the magic of his father’s films, whose personal ideals of imagination, environmentalism, and anti-capitalism seem incompatible with the very concept of amusement parks, traditionally built for distraction, consumerism, and private profit.

Indeed, Ghibli’s Warehouse features multiple shops, selling merchandise ranging from 330 yen (approx. $2.50) postcards to leather bags by Spanish fashion house Loewe retailing over 430,000 yen (approx. $3,500).

I relented in buying a couple postcards and a small enamel pin, but I was ultimately grateful that Ghibli Park challenged me to find joy within myself. Through its design, the park imparts that visitors are the focus, not Totoro, and that is a truly radical idea.

Final Thoughts

While there are no rides, I think any Ghibli devotee will enjoy their experience at the park. The question is if it’s worth the trouble. Ghibli Park is far from Nagoya and further still from international airports; tickets are only available for purchase on the 10th day of every month, with long online waits.

I certainly think international visitors should wait to visit until spring of next year, when the park’s two remaining sections, Mononoke Village (Princess Mononoke) and the Valley of Witches (Howl’s Moving Castle and Kiki’s Delivery Service), will be open.

Will Ghibli Park preserve the studio’s legacy? Will it satisfy the craving for Ghibli? Will it transform Nagoya into an international tourist destination? Will it change the way we experience theme parks? It’s too early to answer any of these questions; all I know is that I’m ready for a movie marathon.